By: Dawn Zoldi

The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma has become one of America’s most advanced proving grounds for autonomous aviation, AI-enabled airspace management and next-generation infrastructure. It does all of this with a laser focus on rural, Indigenous and underserved communities. From its Daisy Ranch test range to a new Advanced Technology Center, the Nation continues to demonstrate how sovereign land, long-term governance and data-driven innovation can turn advanced air mobility (AAM) and beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) operations into tangible public benefits.

From Generational Poverty to Generational Vision

For James Grimsley, the Executive Director of Advanced Technology Initiatives, working with the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma on emerging aviation remains deeply personal. He grew up on the Choctaw Reservation when southeastern Oklahoma was one of the most impoverished regions in the United States, and he is a first‑generation university graduate. His great‑grandmother was born on what is now Daisy Ranch, the Nation’s test facility.

Grimsley’s career arc, from music major to aerospace engineer to policy expert and tribal technology leader, mirrors the interdisciplinary nature of autonomous aviation itself. He began his engineering career working on cruise missiles and early micro air vehicles, long before “UAS” or “drone” were common terms, and later dug into First and Fourth Amendment implications of aerial surveillance with law faculty at the University of Oklahoma.

Over his lifetime, Grimsley has watched technology dramatically equalize access to information. “Anywhere there’s a cell network in the world and someone has a smartphone, they have access to the history of the knowledge of mankind,” he noted. But while connectivity narrowed the information gap between rural and urban America, it did not solve access to critical services.

“What we have not equalized are the other things…and these ultimately really start to boil down to transportation problems,” Grimsley said. In parts of the Choctaw Nation, an ambulance can take 30 minutes to an hour and a half to arrive, which can turn a simple zip code into a predictor of life expectancy and health outcomes.

This is why the Nation has deliberately oriented its emerging aviation programs around life‑saving use cases. “We’re not really focused on convenience items or retail type things right now. We’re focused on the things that directly will impact health,” he explained, such as clinic operations and medical logistics. The Nation aims to use drones, AAM and autonomous systems to leapfrog physical infrastructure limitations in its rural community.

For his part, Grimsley’s experiences, combined with his roots in the Choctaw community, give him an unusually holistic perspective on the intersection of law, technology, sovereignty and rural equity. Today, he translates those decades of technical and policy experience into action. As a result, autonomous aviation is already taking shape on Choctaw sovereign land in Durant, Oklahoma. There, AI‑driven infrastructure, sovereign governance and long‑term thinking converge to solve real problems for real people.

A Sovereign Test Range Built for the Next 30 Years

Long-term thinking is a matter of culture for the Choctaw Nation. When Choctaw leaders first approached Grimsley, they asked what a relevant test environment should look like 30 years from now and how to “future proof” it as much as possible. That question led to Daisy Ranch, a 44,000‑acre property with terrain ranging from flatlands to hills and valleys that closely mirrors military test ranges.

The Choctaw Nation owns the land, exercises sovereign jurisdiction over the surface and can pass its own laws. This creates what Grimsley calls a “true physical test range,” not just an administrative construct. This environment underpins the Choctaw Nation’s role as an official FAA UAS Test Site, a BEYOND Phase 2 participant and the only site currently holding a Section 920(b)(3) waiver, a new statutory authority created in the FAA Reauthorization Act of 2024 that lets the FAA Administrator waive certain underlying statutory requirements in 49 U.S.C. 44711 and their associated regulations for operations conducted under a BEYOND program agreement, as long as the waiver remains consistent with aviation safety.

On the ground at Daisy Ranch, the Choctaw Nation has already built what many consider one of the most mature, operationally grounded BVLOS environments in the country. The Nation engineered the range to support concurrent operations under multiple waivers and approvals, with layered safety mitigations. “We can do what we need to do,” Grimsley explained because the Nation can directly manage ground risk while layering sensors and communications to manage air risk.

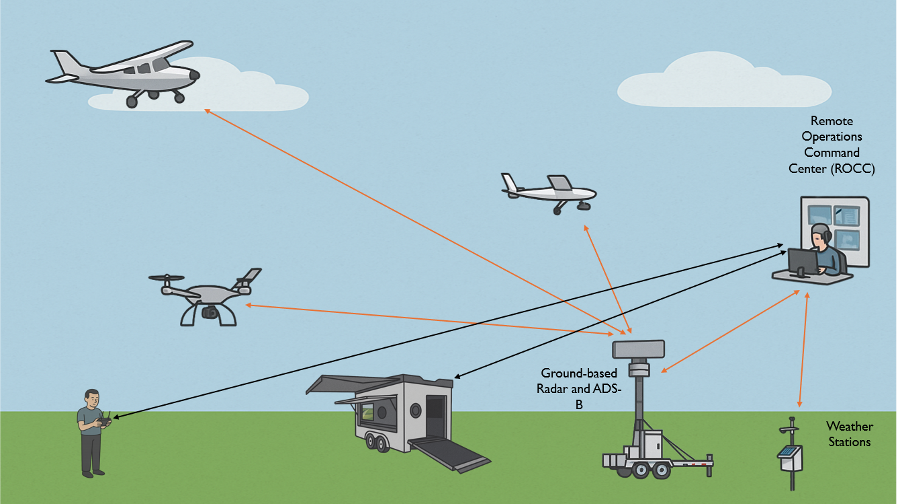

That layered infrastructure now includes multiple radar systems, a closed ADS‑B receiver network and a multi‑band command and control (C2) network covering the range. Key elements include:

- A multi‑sensor detect‑and‑avoid stack: multiple radar types, plus a closed ADS‑B receiver network to track cooperative aircraft.

- A multi‑band communications and C2 network, including first‑of‑type spectrum work, to ensure robust links for BVLOS missions.

- Regulatory tools: from its FAA Test Site status and BEYOND participation to the Section 920(b)(3) waiver, which opens the door to more advanced and repeatable operations.

According to Grimsley, organizations come to the Choctaw Nation in different stages of maturity. Some arrive with mature platforms and simply need a safe, authorized environment to execute operations under existing approvals. Others are at an earlier stage and testing basic viability. For those, Grimsley and his team can help shape realistic concepts of operations and risk mitigations.

The Choctaw Nation also facilitates counter‑UAS work. It can host federal agencies that bring their own authorities under the current Congressional structure for such operations. That combination, BVLOS, AAM, AI‑driven test infrastructure and counter‑UAS, positions Daisy Ranch as a holistic laboratory for the future low‑altitude ecosystem.

AI, Data and the Next Phase of BVLOS

Grimsley works closely with all stakeholders, including the FAA, on one of the drone industry’s most pressing questions: how to safely scale BVLOS and low‑altitude traffic without overwhelming humans or the legacy systems built for a much smaller airspace ecosystem.

He served on the FAA’s BVLOS Aviation Rulemaking Committee (ARC), where industry and government wrestled with safety, policy, technology and public interest tradeoffs. “Technology continues to outpace where we are on the regulatory front,” he noted. “We have very high expectations for safety. We don’t tolerate accidents in the air, and we shouldn’t,” he opined.

Electronic conspicuity, the ability to “see and be seen” in the airspace, continues to be a central issue on the regulatory front in which Grimsley finds himself in a position of influence. He pointed out that systems like ADS‑B were designed in an era when at most 5,000 aircraft were aloft, not tens or hundreds of thousands of uncrewed aircraft and air taxis. He likened ADS‑B to everyone simply shouting at once: “I’m here, I’m here, I’m here.”

AI, he argued, is the only realistic way to manage the complexity and scale of the future airspace. Human operators and controllers are constrained by cognitive load and reaction time, whereas automated systems can “see” in multiple directions, process thousands of scenarios in milliseconds and share learnings rapidly across fleets.

“The reality is we’re seeing systems start to outperform humans,” he said. Grimsley believes properly trained driverless vehicles will eventually outperform human drivers by enormous margins. The same logic applies to collision avoidance and deconfliction for drones and AAM.

But trust and certification remain elusive. Traditional certification frameworks assume deterministic systems involving identical outputs for identical inputs, forever. AI‑based systems, especially those that learn and improve over time, break that model. “Our certification processes are not set up for things like AI,” Grimsley warned.

So how should regulators certify a system whose behavior evolves, even if it is evolving toward safer outcomes? Grimsley envisions emerging “world models,” AI systems trained on sensor data and real‑world observations, not just text, as particularly important for aviation, weather and safety. They have the potential to detect patterns humans simply cannot perceive. According to Grimsley, that same sophistication will also challenge accident investigators, who will have to learn how to “open the AI box and look at cause and effect” when something goes wrong.

Rural Corridors, AAM and the 2030 Horizon

Grimsley emphasized that the Nation approaches all of their work in emerging aviation as a “marathon, not a sprint.” He and his entire team leverages a tribal governance culture that thinks in generational horizons, instead of quarterly earnings.

Grimsley has set an internal target date of 2030. By then, he expects to see widespread adoption of advanced operations and clear differences in how rural and urban business cases evolve. He predicts that rural regions could actually move faster than major cities, because their use cases are rooted in life‑and‑death needs, rather than novelty or convenience. This justifies infrastructure investments. In his view, the forthcoming BVLOS rule (Part 108) will be complex but pivotal. It will send strong signals to UTM providers, cities and states about how to build sustainable operational models

Closer in, regionally, the Choctaw Nation works closely with North Texas, given its proximity to the Dallas–Fort Worth (DFW) metroplex. The next phase of the Nation’s long term plan includes exploring corridors linking DFW and Alliance Airport with Choctaw resources in Oklahoma. This will pave the way for future air taxi and cargo routes across sovereign and state boundaries.

The Nation intends for most of what it builds to become a blueprint for other rural and tribal communities, including the more than 500 federally recognized tribes across the United States. Many of those governments do not have the same resources as the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, the third‑largest tribe in the country, but they share the same challenges of distance, access and the need to translate autonomy into tangible benefits for their people

“We see ourselves as pioneering what it (emerging aviation) looks like for communities that are emerging,” he said. “The problems that we are solving will hopefully be a roadmap for those communities.”

Plugging Into A Grounded Path to Autonomous Aviation

For companies, agencies, researchers and communities who want to move from PowerPoints to flight hours, the Choctaw Nation offers a concrete pathway. “We just tell people to reach out…bring us a proposition,” Grimsley advised. “We’re not good at providing that initial proposition. People bring a proposition; let’s talk about it, figure it out.” The Nation works with agencies, private companies and academic partners. It can support either shared operations or exclusive use of the range for higher‑end campaigns.

To plug in, prospective partners can engage directly with the Choctaw Nation’s Advanced Technology Initiatives team through its public web portals, including UAS‑focused channels and the broader Choctaw Nation site. Bring specific concepts of operation, whether BVLOS cargo, medical delivery, AAM, counter‑UAS or AI‑driven safety systems, for evaluation in the Nation’s test environment under existing waivers and authorities.

As Grimsley put it, the question is no longer whether AI and autonomy will reshape aviation, but how, and for whom. The Choctaw Nation intends to make sure the answer includes them from the start so they foster better healthcare access, safer transportation and new economic opportunities for their own people and other rural, Indigenous and underserved communities like them.Watch James Grimsley on Episode 108 of The Dawn of Autonomy Podcast.