By: Dawn Zoldi

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has spent years trying to educate drone operators into compliance. Now it’s doing something else. When a drone flight crosses certain lines, the agency plans to launch enforcement fast, formally and in a manner that hurts.

This change, they say, is not about punishing the entire community. It’s more about the stubborn reality that clueless, careless, and criminal drone flying has become a consistent problem in terms of public risk, especially near stadiums, near first responders and inside restricted airspace. At the same time, combatant drones have proven globally how quickly they can become a serious security problem.

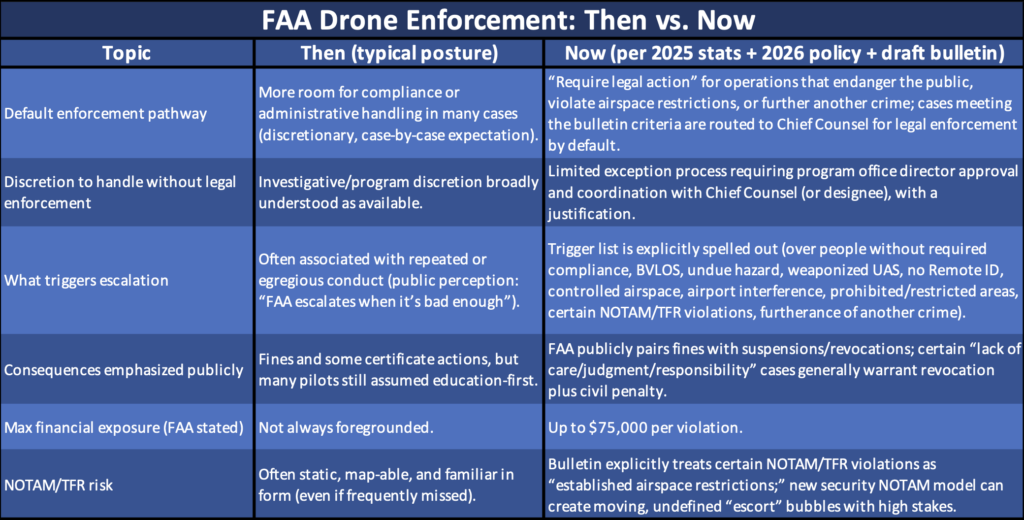

The result: a new Compliance and Enforcement Bulletin (No. 2026‑1), additive to existing policies, which outlines the FAA’s new policy posture. It pushes qualifying cases out of “compliance conversations” and into legal enforcement by default, with certificate consequences and civil penalties on the table early. Because the FAA has now paired that posture with public enforcement statistics and an expanding web of security-driven airspace restrictions, the margin for error for everyday drone operators has become much smaller. Here’s what changed, why it changed now and what drone pilots should treat as a new checklist for staying on the right side of the hammer.

The Problem: A Small Cohort Forces Tighter Rules

Last year alone, the FAA says it fined and suspended or revoked the licenses of multiple drone operators for unsafe and unauthorized operations, including flights near major sporting events, emergency response activities and restricted airspace. In statistics released in early February, the FAA reports that for civil penalties, it levied fines ranging from $1,771 to $36,770 for 18 operations involving violations that occurred between 2023 and 2025, such as:

- $20,371 for restricted airspace near Mar-a-Lago (Jan. 13, 2025)

- $20,370 for operating over people at Sunfest in West Palm Beach (May 5, 2024) where the drone struck a tree

- $36,770 for operating near emergency response aircraft during a wildfire (April 4, 2023)

- $14,790 for operating near State Farm Stadium during the Super Bowl (Feb. 12, 2023)

On certificate action, the FAA says it took enforcement actions in 2025 against eight remote pilots, including suspensions for a drone entanglement with a paraglider (Jan. 7, 2025), multiple safety violations during a drone light show at Lake Eola (Dec. 21, 2024) and operating over people during an NFL game in Baltimore (Nov. 3, 2024), plus a revocation for restricted airspace near Mar-a-Lago (Sept. 7, 2025).

The agency frames these various operations as risks not just to “the public,” but to other aircraft and first responders, exactly the categories of harm that tend to trigger political demand for crackdowns. And so, early this month, reportedly in the spirit of deterrence, the FAA released its updated enforcement policy to require legal action when drone operations endanger the public, violate airspace restrictions or are conducted in furtherance of another crime. That language matters because it swaps the old cultural expectation of “the FAA will try compliance first,” for a new one: “the FAA will route you into legal enforcement if you hit certain triggers.”

The FAA’s Chief Counsel Liam McKenna outlined the agency’s intent. “The FAA will take decisive action against drone operators who ignore safety rules or operate without authorization,” he said. “These unsafe operations create serious risks, and the FAA will hold operators fully accountable for any violations.”

The FAA website also states that drone operators who fly unsafely or without permission can be fined up to $75,000 per violation, and that it can suspend or revoke a pilot’s license. It emphasizes it can fine operators or their companies, even if they don’t hold a license. This appears to be the agency setting the ceiling, publicly, before it starts using more of that ceiling. In short, the FAA seems to have finished debating whether some violations “deserve” enforcement. The only remaining question is how severe the sanction will be.

The Directive Backdrop: “Drone Dominance” By Another Name

Compliance and Enforcement Bulletin No. 2026‑1 directly anchors the posture shift to a Trump Administration directive. It states that on June 6, 2025, President Trump issued the “Restoring American Airspace Sovereignty” Executive Order (EO) and that Section 6 requires steps to ensure full enforcement of applicable civil and criminal laws when UAS operators endanger the public, violate established airspace restrictions or operate in furtherance of an element of another crime. That not-so-subtle direction drove the current governance choice to treat certain UAS misconduct less like a training failure and more like a law-enforcement problem.

And so in its public 2026 web statement, the FAA says updated policy to require legal action when operations endanger the public, violate airspace restrictions, or further another crime, the same three-part trigger in the EO and which the FAA’s draft bulletin formalizes.

Here’s the flow. “Until further notice,” when someone operates a UAS in a way that endangers the public, violates established airspace restrictions or is in furtherance of an element of another crime, FAA investigative personnel will send the case to the Chief Counsel for legal enforcement action. It further states that compliance and administrative actions will not be used except as permitted by the bulletin. This is the “hammer”: a routing rule that makes legal enforcement the default, not the escalated option.

The bulletin then narrows discretion to a gated exception process: in limited instances, program offices may forgo referring a case to the Chief Counsel only with approval of the program office director and the Chief Counsel (or designee), and the director must provide a justification as part of the coordination. That matters operationally because it shifts the burden. The system has to justify mercy, rather than justify escalation.

The Pilot-Facing Categories That Trigger The Hammer

The bulletin lists specific conduct the FAA will treat as qualifying for purposes of its enforcement hammer.

UAS operations that “endanger the public” include operations over people when 14 CFR § 107.39 and Subpart D (operations over people or OOP) are not complied with, BVLOS in violation of 14 CFR § 107.31, creating an undue hazard to persons or property in violation of 14 CFR §§ 107.19(c) or 107.23(b), and operation of a weaponized UAS in violation of 49 U.S.C. § 44802.

UAS operations that violate “established airspace restrictions” include operating without Remote ID in violation of 14 CFR § 89.105, operating in controlled airspace in violation of 14 CFR § 107.41, interfering with airport operations and traffic patterns in violation of 14 CFR § 107.43, operating in prohibited or restricted areas in violation of 14 CFR § 107.45, and operating contrary to certain NOTAMs/TFRs (citing 14 CFR §§ 91.137–91.145 and 99.7) in violation of 14 CFR § 107.47.

The bulletin also states that UAS operations under other regulatory schemes, such as 14 CFR parts 91, 135, or 137, will be treated the same as those described for Part 107 operations. And for “another crime,” it takes an expansive view: operation of a UAS in furtherance of an element of another crime includes all federal crimes.

The Biggest Teeth: The General Path of Revocation-Plus-Penalty

The draft bulletin also signals a sanction philosophy for remote pilot certificate holders. It says the FAA has observed a proliferation of regulatory and statutory violations that evidence a lack of qualifications due to a lack of care, judgment, or responsibility, and it announces sanction guidance to address such violations more effectively.

Then it lays down the part that should make any Part 107 operator sit up: when a remote pilot certificate holder engages in operational conduct demonstrating a lack of care, judgment or responsibility, the FAA generally will proceed with both (1) remedial legal enforcement action to revoke the remote pilot certificate and (2) punitive legal enforcement action in the form of a civil penalty for any regulatory violation.

It also states that such UAS violations generally warrant revocation not only of the remote pilot certificate but also of any other airman certificate (excluding airman medical certificates) or ground instructor certificate held by the violator. The significance of this lies in the fact that the FAA will move beyond fines and will treat certain UAS behavior as a qualifications failure that can cascade across certificates. These are career-and business-impacting outcomes.

The Practical Choke Point: Enforcement Reach vs. Capacity

The bulletin scales enforcement by changing internal decision rules (mandatory legal referral, limited exceptions and explicit coordination when criminal statutes may be in play) Specifically, when FAA investigative personnel believe there may be a violation of any federal or state criminal statute, they must coordinate the matter as described in the order. FAA employees also have the option of reporting suspected violations via direct referral to the DOT OIG hotline.

But the order does not create new bodies in the field. It also does not appear to deputize local law enforcement to act as FAA enforcement personnel or grant them FAA regulatory enforcement authority. So the realistic model remains in play. Local law enforcement may be first on scene, but FAA legal consequences still hinge on federal investigation, evidence and case processing, often after the fact.

Jennifer Ambrose, an 18 plus-year FAA Office of the Chief Counsel veteran, and founder of Aviation Aerospace Law, PLLC weighed in on this. “It’s unclear how this will play out in practice.” She continued, “Certainly this signals that the FAA is taking a harder line on enforcement than its previous ‘compliance philosophy.’ Whether that translates into more enforcement actions will largely depend on whether the FAA has the resources to follow up with enforcement.”

Roving-Bubble NOTAM: Moving Targets Meet Mandatory Legal Action

Autonomy Global’s analysis of the FAA’s nationwide UAS security NOTAM (FDC 6/4375) captured the compliance risk of newly announced broad, mobile restrictions. In that piece, we outlined how the NOTAM designates airspace near certain DHS/DoD/DOE facilities and mobile assets as “national defense airspace,” applies to “vessels and ground vehicle convoys” and their “associated escorts” (which we noted are undefined), and imposes a stand-off of 3,000 feet laterally and 1,000 feet vertically where UAS operations are prohibited unless authorized. The NOTAM’s enforcement language says that operators deemed a credible safety or security threat to protected personnel, facilities, or assets may be “mitigated,” when permitted, via interference with, interception of, seizure of or destruction of drones deemed threats.

Now connect that to this enforcement bulletin. The bulletin explicitly lists “operations contrary to a NOTAM” (of the specified types) as violating established airspace restrictions. And the FAA’s public policy statement says those airspace-restriction violations now require legal action. Ambiguity on the front end combined with less discretion on the back end compounds the effect of the NOTAM.

Kerry Fleming, who worked for the FAA for almost four decades including as the former FAA Airspace Manager of the System Operations Support Center (SOSC) said, “I am immediately suspicious of the ‘coincidences of timing.’ I believe this is in direct support of the recently outrageous ‘mobile’ TFR FDC 6/4375 that covers moving DOD, DOJ, and DHS assets (vehicles) including personnel (agents).” He further opined, “This administration is determined to put all UAS operators on notice that they face severe penalties if they violate restricted or prohibited airspace, whether purposely or accidentally. This also appears to effectively modify the FAA’s role of simply being the regulatory authority for a safe and efficient national airspace system.”

The Hammer’s Edge: Safety First, Clarity Second

Keeping skies safe and secure is a goal almost everyone in this industry shares. And the FAA is right to focus on the small fraction of operators whose flights near stadiums, first responders and restricted airspace create outsized risk. But the way the agency has chosen to get there matters. Pairing moving, security-driven “don’t-fly” boundaries with a policy posture that presumptively routes qualifying cases into legal enforcement changes the risk calculus for every serious operator, not just the reckless ones. Certain conduct will no longer be treated as a correctable mistake, but as a qualifications and deterrence problem, where revocation and civil penalties can often come together. If this is the new baseline, the real test will not be whether the hammer exists. It does. The real issue is whether the lines are clear enough, the process is consistent enough and the enforcement capacity is actually credible enough to punish true bad actors, without turning ordinary compliance into a moving-target trap for everyday drone pilots.