By: Dawn Zoldi*

By midnight January 8th, the FAA’s official public comment period on its Draft Programmatic Environmental Assessment (PEA) for Drone Package Delivery Operations quietly closed with only a handful of voices on the record, despite the document’s national implications. Notice first appeared in the Federal Register on December 9, 2025, with comments due by January 8, 2026. Although state attorneys general from Washington and New York sought a 45‑day extension, the agency declined to broaden the window for substantive engagement.

As of the date of publication, regulations.gov shows just a dozen posted comments, showing just how thin the public file remains for a framework that could shape low‑altitude airspace for decades.

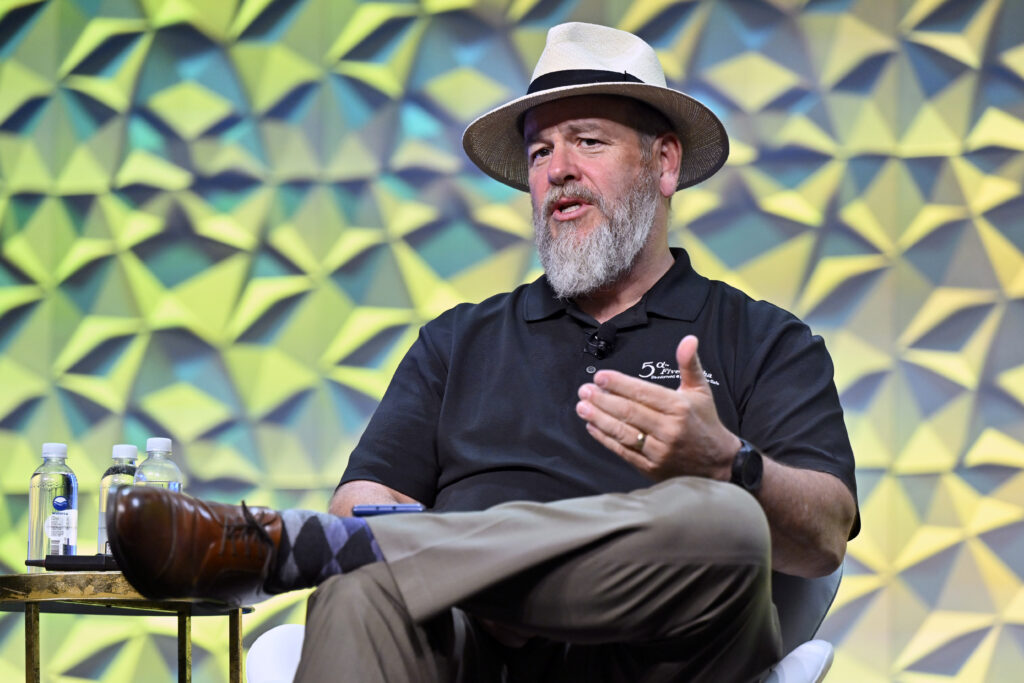

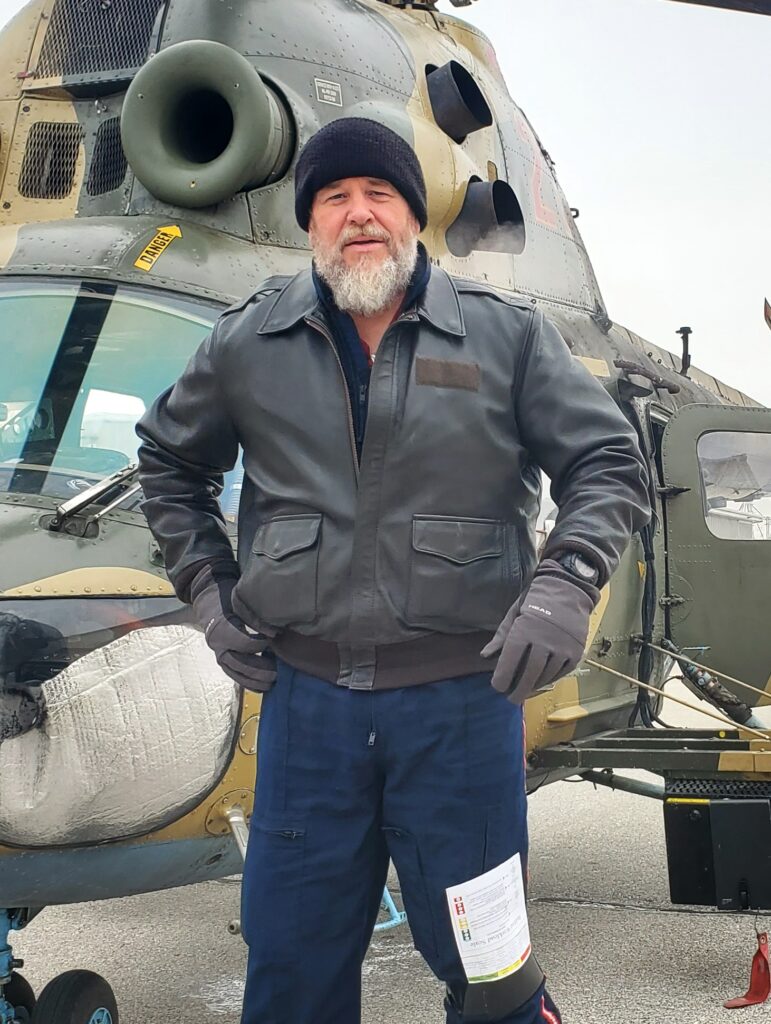

The hope now is that technically grounded submissions like those from Autonomy Global Infrastructure Ambassador Rex Alexander are treated as more than a procedural checkbox and instead drive real changes to a PEA that still leaves fundamental safety and infrastructure questions unresolved.

The draft PEA for Drone Package Delivery Operations aims to create a nationwide environmental framework for Part 135 drone deliveries, but from the vantage point of Autonomy Global Infrastructure Ambassador Rex Alexander, it leaves critical safety, infrastructure, and data integrity questions unanswered. The result is a document that risks normalizing large-scale drone delivery without fully aligning with the safety architecture of the National Airspace System (NAS) or the realities of existing heliport and vertiport operations.

What the FAA’s Draft PEA Actually Does

The draft PEA evaluates the “reasonably foreseeable” environmental impacts of commercial drone package delivery conducted under Part 135 across the United States, treating package flights from local hubs to customers as a single nationwide program rather than a series of isolated projects. It is designed to streamline future approvals through the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)’s “tiering,” meaning later project‑specific reviews will lean heavily on this PEA unless local conditions demand more analysis.

The proposed operations assume electric-powered drones flying primarily from commercial‑area hubs, with most environmental scrutiny focused on noise exposure, while other categories such as air quality, land use, and socioeconomics, are largely screened out on the basis that drones are small, electric, and sited at existing developed locations. Noise is treated as the dominant potential impact, with the PEA defining a per‑hub “unit capacity threshold” of 1,150 average annual day deliveries as the level of activity it evaluates, and expecting operators to provide aircraft noise data to show they fit within that envelope.

Safety and Environmental Review Cannot Be Separated

Alexander argues that the PEA treats environmental review as if it can be cleanly separated from the FAA’s statutory duty to ensure safety in the NAS, when in fact safety, infrastructure, and environmental outcomes are tightly interwoven. Decisions about where hubs are located, how flight corridors are structured, and how separation from other aircraft is maintained all directly influence risk to people and property on the ground, as well as cumulative environmental effects over time.

Instead of anchoring these questions in established regulation, advisory circulars (ACs) and transparent national standards, the PEA leans heavily on operator‑specific Part 135 Operations Specifications (OpSpecs) to manage issues like site suitability, safety buffers and operational constraints, an approach Alexander sees as inherently unstable. OpSpecs are regionally interpreted, not publicly accessible, and were never intended to function as de facto infrastructure standards that shape how and where aviation facilities proliferate, which weakens both safety predictability and environmental accountability, in Alexander’s opinion.

This makes sense. A well‑constructed programmatic National Environmental Policy Act review should grapple with, and that includes the infrastructure footprint of drone delivery, not just the flights themselves. Under NEPA and FAA’s own implementing order, programmatic reviews are meant to address broad programs and connected actions, such as policies, operational concepts, and the associated facilities and infrastructure, so that later tiered reviews have a defensible foundation.

For a nationwide Part 135 drone package program, the “action” is not only aircraft moving through airspace but also the creation and use of drone ports, approach and departure paths, and separation schemes that affect people, property and other aviation users on the ground and in the air. Programmatic NEPA guidance explicitly notes that infrastructure scenarios are a core element of these broad reviews, which supports Alexander’s position that questions about hub classification, heliport protection, data integrity, and safety buffers are squarely within the appropriate scope of the PEA rather than optional side issues.

Misnamed “Hubs” and the Missing Drone Port

One of Alexander’s most pointed concerns is the PEA’s repeated use of the term “HUBS” to describe fixed drone takeoff and landing locations, a label that sidesteps existing regulatory definitions and obligations. Under 14 CFR 157.2, any designated area for aircraft landing and takeoff, whether an airport, heliport, vertiport, gliderport, or other aircraft landing area, falls under the airport definition, which brings with it notice and evaluation requirements under 14 CFR 157.3.

From Alexander’s perspective, the sites described in the PEA plainly function as airports and should be processed under Part 157, documented in FAA infrastructure databases, and visible to other airspace users and land‑use authorities as aviation facilities, not treated as generic logistics “HUBS.” He urges the FAA to adopt a clear “Drone-Port” classification aligned with existing airport and heliport taxonomy, both to trigger the right regulatory mechanisms and to support consistent, nationwide environmental and safety assessments tied to recognizable infrastructure categories.

Who Sets Separation Distances and Safety Buffers?

The PEA signals that separation distances for non‑participants and nearby properties may be defined in operator manuals, effectively delegating what Alexander views as a public safety decision to individual companies. For an Infrastructure Ambassador who works across manned and unmanned domains, that is a fundamental red flag. Separation distances that govern how close drones may operate to homes, streets, schools, and workplaces should be federally defined, performance‑based, and applied uniformly.

Alexander emphasizes that these distances must be grounded in aircraft performance, downwash, failure modes, and quantitative risk modeling, and not left to operator preference. Inconsistent buffers translate directly into uneven risk exposure for communities and bystanders. Without clear national minima for lateral and vertical separation, the PEA’s environmental conclusions rest on assumptions about public protection that have never been codified or tested in a transparent, standards‑based framework.

Data Gaps, UTM and Invisible Heliports

The draft PEA leans on UAS Traffic Management (UTM) as a key element of how risks will be mitigated for low‑altitude drone operations. However, Alexander notes that UTM is only as good as the infrastructure data it depends on. Long‑standing gaps in FAA inventories of private‑use airports and heliports, including thousands of uncharted hospital heliports highlighted in a 2019 NASA report (ACN: 1599969), mean that any reliance on digital traffic systems risks routing drones through approach and departure paths that are effectively invisible in official datasets.

From an infrastructure‑centric perspective, this is not a theoretical problem. At 400 feet above ground level (AGL), a drone flying over level terrain can penetrate a standard heliport or vertiport approach surface within a few thousand feet of a final approach and takeoff area. This creates an obstruction hazard under existing FAA criteria. Alexander points out that in elevated terrain, these conflicts can extend out to the 5,000-foot distance identified in 14 CFR Part-77.9 and the FAA Heliport Design AC 150/5390-2D regarding obstructions requiring notice. He urges the FAA to establish a minimum 5,000‑foot lateral separation from heliports and vertiports for drone routes unless and until infrastructure data integrity is substantially improved.

Hospital Heliports and Emergency Access at Risk

One of the most sensitive blind spots, in Alexander’s view, is the PEA’s limited treatment of hospital heliports and other fixed‑site facilities that support emergency medical and public safety operations. Section 2209 of the FAA Extension, Safety, and Security Act contemplates protections for such sites. But the draft PEA does not convincingly explain how hospital heliports, many of them missing from FAA databases, will be identified, protected, and kept free from cumulative encroachment by routine commercial drone traffic.

Alexander frames this not merely as an airspace deconfliction issue, but as a resilience and equity concern. Drones carrying consumer packages should never degrade access, safety margins, or response times for aircraft transporting patients, blood, organs, or critical medical staff. Without robust mapping of hospital heliports, conservative separation criteria, and explicit prioritization of emergency aviation operations, the PEA risks normalizing a background level of conflict that may only become visible after an incident.

Adequacy, Accountability and the Path Forward

The PEA does not fully explain how operators will demonstrate compliance with 14 CFR 135.229, which requires that each takeoff and landing area be adequate for the aircraft and operation involved. This gap, Alexander highlights, presents both a safety and environmental problem. In the absence of FAA‑defined infrastructure standards for drone ports, questions of “adequacy” devolve into case‑by‑case judgments embedded in non‑public OpSpecs, making it difficult for communities, other airspace users, or even regional FAA offices to understand or challenge the criteria being applied.

From Alexander’s vantage point, a responsible national framework for drone package delivery must rest on a few foundational steps:

- Recognize drone hubs as airports under Part 157

- Establish a formal Drone Port classification

- Publish a dedicated advisory circular for drone operational infrastructure

- Federally define separation distances and safety buffers, and

- Systematically correct aviation infrastructure data before leaning on UTM or tiered NEPA shortcuts.

Without those elements, the FAA risks endorsing a future in which drone delivery appears environmentally benign on paper while remaining misaligned with the safety framework that has long underpinned public trust in U.S. aviation.

*This article was based largely on Rex Alexander’s Public Comments to the PEA, with his permission.

EDITOR ADDENDUM 1/14/26: Without much fanfare, the FAA did extend the date until the 23rd of January: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2026/01/05/2025-24237/notice-of-extension-of-public-comment-period-for-the-draft-programmatic-environmental-assessment-for

Here is the original website that that is still up and running that has the closure date listed as January 8th and has Rex Alexander’s comments and 11 other listed: https://www.regulations.gov/document/FAA-2013-0259-4288

Here is the new website that is also up and running that has the closure date listed as January 23rd, but all new comments: https://www.regulations.gov/document/FAA-2013-0259-4312