By: Dawn Zoldi

From self-driving cars and underground drones to unmanned maritime craft, autonomous vehicles in the air, on land and at sea all live and die by their positioning, navigation and timing (PNT) stack. Without trusted PNT, precision mapping collapses, navigation fails in GNSS-denied environments and lethal autonomous weapon systems (LAWS) raise even more profound operational and ethical questions. Those PNT threads ran through every segment of this Full Crew “Autonomy” episode, as guests Justin Thomas (Exyn Technologies), Pramod Raheja (Airgility) and Karson Kall (WISPR Systems) joined to unpack the tech, tactics and tough policy issues shaping the future of autonomy.

Space-Based Precision: The Right Answer for Autonomy?

Karson’s pick, “CHC Navigation Discusses How Network RTK Enhances Global Positioning Accuracy,” drilled into how satellite-based wide area augmentation can deliver survey-grade position without the traditional constraints of local bases and network coverage.

The article explained how CHC Navigation’s Satellite-based Wide Area Augmentation Service (SWAS) leverages a constellation of reference stations, cloud-based ionospheric and tropospheric modeling and L-Band satellite broadcasts to push GNSS accuracy from meters down into the sub-3 cm horizontal and sub-6 cm vertical realm, all while eliminating the need for a local RTK base station.

Karson broke it down in plain language. He reminded everyone that “we’re all used to hearing about GPS” but what really matters is leveraging “the GNSS constellation, that global navigation satellite system” including GPS (U.S.), GLONASS (Russia), Galileo (Europe), BeiDou (China) and other constellations. He described how atmospheric distortion historically kept accuracy from being “survey grade,” where “we’re trying to get our XYZ points all within that golf ball size as a repeatable pattern.” With SWAS-style satellite corrections, “you have a clear view to the sky and receive corrections.” This enables centimeter-level performance without being “landlocked” by ground networks, Wi‑Fi or cellular connectivity.

Justin immediately honed in on what this kind of all-space solution means for real autonomy. As “someone who develops autonomous systems,” one of the things he cares “a lot about is latency,” and he is “particularly curious about the real-time aspects of this” when you move from post-processed surveying into “a real-time system operating autonomously.” He also pointed out that routing everything through space and back again adds more links in the chain: satellites down to the ground, back up and then down to the vehicle. At the same time, operators are already wrestling with ionospheric distortions, timing issues and “atomic clock issues.” That raised an implicit question: how far can a purely space-based correction architecture go before latency and vulnerability become limiting factors for dynamic robotic platforms?

Pramod’s take underscored how mission profiles will drive whether this flavor of PNT makes sense. He agreed with Justin that “it depends on the mission… what are you doing,” noting that in some of the commercial applications Karson highlighted, such as precision agriculture and certain surveying jobs where “you don’t need it real time, but you do need the data,” satellite-based corrections that converge more slowly may still be perfectly acceptable. By contrast, he pointed out that “as we get to the third article,” (below) there are “some things that happen real time where having the ability to operate in the GNSS denied environment is very, very important.” Relying solely on a space-layer augmentation could be a liability for time-critical defense and security missions.

As someone who spends a lot of time around surveyors, mappers and builders, it was impossible not to connect this to real-world use. As I noted on-air, this level of PNT precision is “really critical for precision surveying, mapping, precision agriculture, construction… that AEC crowd of architecture, construction and engineering… especially if they’re going to be using drones to help gather that data.” It also represents a fascinating inversion of the U.S. government’s long-running search for alternative PNT. The Department of Transportation (DoT), for example, has been exploring ground-based GNSS augmentation for years, yet here we see a private company “just going to throw out their own augmentation… and throw it out in space.”

That move, however, may raise a strategic eyebrow. As I pointed out, “we’re seeing a lot of attacks in space. We’re seeing spoofing, we’re seeing jamming… and other issues with weather,” which makes an all-space, all-the-time approach to positioning a double-edged sword for autonomy.

Karson acknowledged that, out in the field, on the rover side he’s already seen “pretty consistent results” with satellite corrections, but he is “curious to see how it all actually plays out once fully in effect” for drones and other dynamic platforms.

In many ways, this segment set the stage for the rest of the show: space-based precision is an incredible enabler for autonomous operations, but only when its latency, resilience and mission-fit are understood in the broader PNT and autonomy stack.

GNSS-Denied Navigation: Accuracy Without GPS

From “P” in PNT we transitioned to “N” with Justin’s selection, an academic paper titled “GNSS-denied unmanned aerial vehicle navigation: analyzing computational complexity, sensor fusion, and localization methodologies.”

This dense but important survey walks through how UAVs navigate when GNSS is obscured, degraded or outright denied. It classified approaches into Absolute Localization (AL) and Relative Localization (RL) and highlighted the growing power, and limitations, of vision-based and multi-sensor fusion approaches. It underscored that no single sensor or algorithm is sufficient. Robust autonomy comes from fusing cameras, LiDAR, inertial measurement units (IMUs), radar and more, then running them efficiently enough to work in real time.

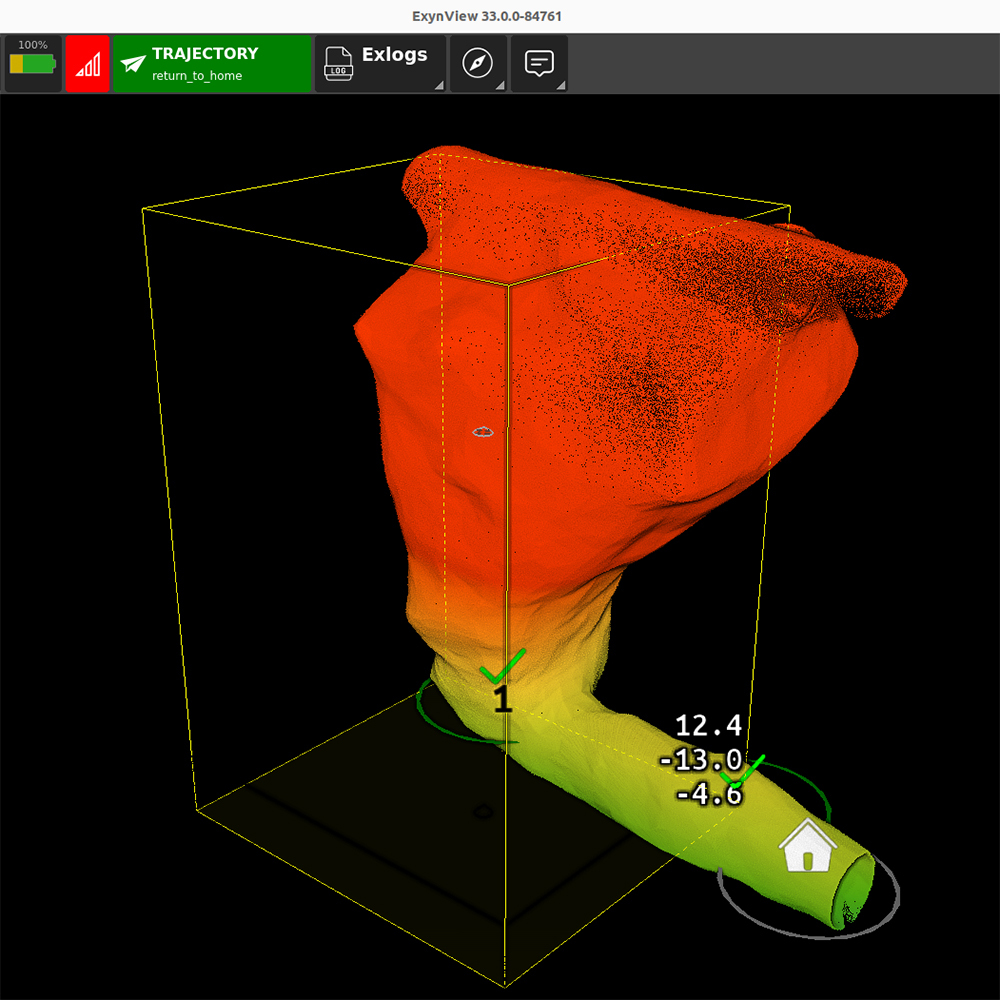

Justin connected the paper directly to Exyn’s mission. Many of their customers are “underground mining companies” blasting “large caverns underground” that must be surveyed and mapped to plan subsequent operations, in places where “there’s no realistic way for GPS to be useful… sometimes these are kilometers underground.” In those settings, autonomy is “still necessary because they need this information,” so vehicles “end up localizing using relative methods,” figuring out “where they started, where they’re trying to go” and “using only local information” rather than any global Earth-fixed frame.

He offered a succinct definition of that relative approach. The vehicle “doesn’t actually need to know or doesn’t have the ability to know where it is in the world,” so instead of latitude/longitude/altitude it determines “where it is relative to where it started” or to a reference established before flight. For Exyn, that means LiDAR-based SLAM (simultaneous localization and mapping) where the system is “constructing a 3D model of the world that they’re in and simultaneously using that model to figure out how the vehicle is moving in that world,” ingesting “thousands and thousands of points per second” in 3D point clouds.

The article expanded beyond LiDAR to cover visual odometry, visual-inertial navigation, terrain contour matching, digital scene matching and semantic mapping, but its core conclusion mirrored what all the panel experts see across autonomy: multi-sensor fusion is non-negotiable.

As I put it, “one sensor only gives you a certain perspective,” so “if you can incorporate LiDAR, radar, other sensors, you’re going to get a better view and determination of where you are,” much like “a multi-layer defense” for counter-UAS where no single modality is a silver bullet. Justin agreed, adding that each sensor has “some drawback” and that fusion “goes a long way to improving reliability and accuracy and precision.”

Pramod reinforced this with a ground-vehicle example that most of the audience could visualize. He pointed to Waymo’s driverless taxis, which “employ a hybrid fusion… they have LiDAR… they have quite a few cameras… and they also employ some radar,” and contrasted that with a purely vision-based approach. In his view, “a hybrid fusion of sensors [is] the future… whether it’s drones or cars or trucks,” and the autonomy industry is converging on that model.

Karson added that even in today’s GNSS-reliant systems, “we’re blending multiple sensors,” such as RTK GNSS, barometers and IMUs, on a network that can “kick out” a sensor when it disagrees with the others. Fusion underpins resilience even before you get to fully GNSS-denied environments.

Justin also flagged a blind spot he sees in the literature. Too many “navigation” papers focus on localization alone. For him, true navigation is “navigating around obstacles,” and “none of the absolute methods really allow you to do that directly.” Even a perfect GPS fix “is not going to tell you where a tree is” if you want to “fly under a tree canopy,” so relative, perception-driven methods that build and update a live model of the environment are essential. That nuanced distinction, between knowing where you are and being able to move safely through the world. will only become more important as autonomy pushes further into cluttered, contested and confined spaces.

LAWS: Timing, Targeting and Ethics

After spending two segments on positioning and navigation, we turned to perhaps the most fraught application of PNT: lethal autonomous weapon systems. Pramod’s article choice, “Cheap Drones, Expensive Lessons: Ethics, Innovation, and Regulation of Autonomous Weapon Systems,” traced how rapidly evolving drone warfare, from Ukraine to Libya to emerging U.S., Russian, Chinese and Turkish programs, challenges existing legal, ethical and regulatory frameworks. It outlined how autonomous weapon systems (AWS) are categorized by human involvement (in-the-loop, on-the-loop, out-of-the-loop) and tracks the race dynamics driving mass production, AI-enabled targeting and swarming.

On the show, Pramod grounded this in what he called “the most visible war ever” between Russia and Ukraine, where “every day there’s a new drone video on YouTube,” making the operational impact and ethical stakes of autonomy painfully public. He cited “Operation Spiderweb” on June 1, when Ukrainian forces used drones to strike Russian airbases, as a “huge wakeup call” for parts of the U.S. government, even though many in industry already knew this was possible and likely. In parallel, he pointed to the sheer scale of Russia reportedly producing “over one million drones in a single year,” and to China’s goal of global AI dominance by 2030, backed by a large defense budget and swarming demonstrations with about 1,000 drones.

We also explored how the U.S. is responding. The article notes that the Pentagon has launched a multiyear effort to equip each combat division with roughly 1,000 drones across missions. It also updated Directive 3000.09 in 2023 to shift from “human” to “operator” oversight. language some worry could open the door to AI or non-traditional entities in supervisory roles. The Department of Defense (DoD) also uses Project Maven as an example of “ethical AI,” where machine learning automates the analysis of drone imagery while humans ostensibly retain the authority over lethal decisions. This is where PNT meets policy: if a system can autonomously sense, classify, localize and target with high confidence and low latency, the temptation to push humans further “out of the loop” grows.

The article and discussion both stressed that Lethal AWS (LAWS) may lower the threshold for conflict in ways nuclear weapons did not, because they can be deployed at lower cost, in greater numbers and with less political friction, especially if casualties are primarily on the other side. That’s part of why UN Secretary-General António Guterres has called LAWS without meaningful human control “politically unacceptable and morally repugnant,” and urged states to pursue legally binding limits by 2026.

Pramod underscored that while the U.S. has historically been “very cognizant” of ethics on the battlefield, “our adversaries… are not necessarily thinking about that as much,” which creates an asymmetry between operational necessity and normative restraint.

Throughout, the panel kept coming back to accountability in LAWS: algorithmic bias in targeting, the difficulty of applying distinction and proportionality when a model misclassifies and the need for rigorous testing, transparency and diverse teams to mitigate those risks.

In my view, LAWS are the ultimate stress test for autonomy’s PNT foundations. The same precise positioning that enables safe construction staking can enable precise strikes; the same GNSS-denied SLAM stacks that keep miners out of harm’s way can help munitions hunt through urban canyons. The same sensor fusion that makes autonomy robust can make it frighteningly effective. That’s why, as this episode showed, the autonomy community must talk about operations and ethics in the same breath. And keep PNT at the center of both conversations.