By: Tracy Reynolds, AG Space and Maritime Ambassador

Remember playing dodgeball? What about the sting of taking one of those balls right in the face? Did you know an average elementary school-aged student throws a dodgeball at about 25-35 miles per hour? Now imagine that ball traveling at about or approximately 17,000 miles per hour. That’s the approximate speed of space debris traveling around the Earth in low Earth orbit (LEO) which shares the same orbital space as satellites that contain sensitive components and payloads. Its projected average impact speed is faster – about or 22,300 miles per hour (or 10 kilometers per second). That’s faster than a speeding bullet.

You don’t have to be an engineer or scientist to understand the damage space junk can wreck upon satellites. An elementary school student can grasp that a high speed collision between sensitive electronic components and a fast moving piece of junk could result in total loss.

Imagine it. Starlink satellites cost approximately $1,000 per kg, with about $17 to 18 million worth of Starlink satellites on each Falcon 9 launch. The Falcon 9 launch costs about $62 million, though it may drop to $30 million per launch as the rockets become more and more reusable. But even with those “cost savings” space junk can wipe out millions in an instant.

Trash In Space: The 411

Space junk, as an impediment to free movement in space and an obstacle to future investment, is currently in the news – but the problem is not new. In 1978, NASA scientists Don Kessler and Burton Cour-Palais predicted the Kessler Syndrome or when the amount of space debris would grow from collisions alone rather than new launch activities. NASA created the Orbital Debris Program (OPDO) in 1979 soon after the visible reentries of Cosmos 954 and Skylab in 1977 and 1979 respectively. To be more succinct, space junk is older than Britney Spears. It’s time to stop admiring the problem and take action to solve it.

The Size of the Problem

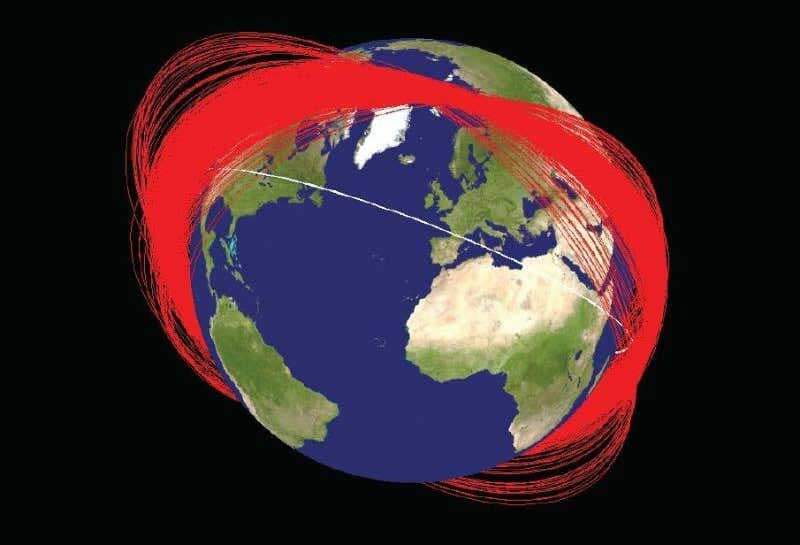

Space debris in LEO consists of about 6,000 tons of human-created junk, some the natural consequence of machines in space and other stuff more deliberately created. The deliberate destruction of the Chinese Fengyun-1C spacecraft in 2007 and the accidental collision of an American and a Russian spacecraft in 2009 increased the large orbital debris population in LEO by approximately 70%. Such debris can be small or quite large.

Small space debris measures, on average, from about 2.5 to 25.5 inches (1 to 10 centimeters). It includes paint flakes to abandoned vehicle stages, non-functional satellites and fragments resulting from collisions or explosions.

Not all space debris is small. In 2021, a global consortium from 13 countries identified the top 50 statistically-most-concerning derelict objects in LEO. This list provides a starting point for debris remediation firms to hone their business plans. The majority of objects that pose the greatest debris-generating risk were deposited before debris mitigation guidelines were put in place. For example, rocket bodies pose the greatest debris-generating risk in LEO.

The Potentially Big Impacts

While space debris can be small, its impact can be mighty. The Aerospace Corporation, a leading architect for the nation’s space programs, notes that a piece of space debris the size of a blueberry can create the impact of a falling anvil.

This debris hinders the use of space upon which critical infrastructure and economies rely, such as communications, national security, financial exchanges, transportation and climate monitoring. Debris increases the costs of space operations by requiring efforts to shield against or maneuver around it, threatens the safety of astronauts and satellites, limits the ability to launch spacecraft and may eventually make entire orbits unusable.

Space debris is a global problem.

International Bodies Answering the 911

Clearly, space debris is a global problem. Individual nation states and corporations can take (and are taking) individual action. However, coordination, collaboration, and mutual intervention is needed to truly address space junk.

A COPUOUS Amount of Work To Be Done

One of the primary drivers of space policy, the UN Committee on the Peaceful Use of Outer Space (UNCOPUOS), promotes international cooperation in the peaceful exploration and use of outer space. This organization focuses on scientific and technical issues like space debris, spaceflight safety and the use of space-based assets for disaster management. UNCOPUOS also considers legal issues, such as legal aspects of space traffic management or space resource activities.

The U.S. was one of the founding 18 members of UNCOPUOS in 1958 and has utilized the committee and its subcommittees to build international support for U.S. space policies and a vision for expanding human presence in space. U.S. participation in UNCOPUOS is guided by the U.S. National Space Policy (NSP) released in 2020 by the first Trump administration. The NSP calls for us to encourage and uphold the rights of nations to use space responsibly and peacefully, lead, encourage and expand international cooperation and create a safe, stable, and secure environment for space activities.

Laws That Are Out of this World

UNCOPUOS played a key role in the development of the outer space legal regime. The Soviet Union’s launch of Sputnik in 1957, followed closely by the U.S. launch of Explorer 1 in 1958, led to global concerns about an arms race in outer space. As a result, UNCOPUOS drafted the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, the foundational outer space treaty and bedrock of the outer space legal regime. 115 countries are now a party to it.

The Outer Space Treaty has 13 key articles. The most relevant to space debris include the following:

- Article I states that exploration and use of outer space must be carried out for the benefit of, and in the interests of, all countries.

- Article III requires that the exploration and use of outer space must be carried out in accordance with international law.

- Article VI notes that States bear international responsibility for national activities in outer space, whether those are conducted by governmental agencies or by non-governmental entities.

In addition to this list, under the treaty, States must authorize and provide continuing supervision of activities by non-government entities and retain jurisdiction and control over objects they register. In addition, States must also conduct all activities with due regard to corresponding interests of other State Parties consult other State Parties if they anticipate causing potentially harmful interference.

Besides the Outer Space Treaty, the UNCOPUOS developed 21 Long-term Sustainability of Outer Space Guidelines. This set of voluntary, non-binding guidelines covers a range of topics that include: safety of space operations, the practice of registering space objects, international cooperation to ensure emerging space-faring nations can implement guidelines, sharing of space weather data and risks of uncontrolled re-entry of space objects. While these are non-binding principles that each member State can determine how to implement, they set – for the first time – an internationally agreed minimum standard of behavior by States engaged in space activities.

Other Players In This Space

A variety of other international organizations seek to address legal and practical issues regarding space and space debris as well:

- The UN General Assembly’s First Committee covers disarmament and international security. Their agenda and annual resolutions address a range of issues on space security, including norms, rules and principles of responsible behavior in space.

- The Conference on Disarmament in Geneva is a multilateral disarmament negotiating body which considers space arms control among other issues. This body reports to the UN General Assembly in New York.

- The International Telecommunications Union (ITU) covers international cooperation in telecommunications, allocates global radio spectrum and satellite orbits and develops technical standards.

- The International Telecommunications Satellite Organization (ITSO) works to ensure that satellite communications are accessible to all nations globally.

- The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) does not regulate outer space but it does regulate aviation. The ICAO plays a key role in promoting international cooperation regarding space travel and space travel’s impact upon aviation and aviation’s impact upon space trave

Slow But Steady Can Win the Race

Despite the variety of intentional bodies, applicable legal “rules” and other initiatives underway, there are serious drawbacks to the creation of global policy. The UNCOPOUS, for example, operates completely by consensus. This means that decision making is slow. Very slow. UNCOPUOS took about 10 years to develop those Long-term Sustainability of Outer Space Guidelines. And that was with dedicated U.S. leadership and guidance. Of note, the U.S. is one of only a few nations interested in the perspective of private corporations. This unique relationship gives voice to an important stakeholder in the space debris fight.

Until recently, the U.S. has engaged with other States on space situational awareness and space traffic in UNCOPUOS. Given the increased activity and objects in space, it is increasingly important that a global solution to prevent collisions and protect U.S. national and commercial interests in orbit, as well as continued access to space. But the U.S. may be driving in a different direction.

Trump 2.0: Manifest Destiny In Space?

In his inaugural address, President Trump said that “we will pursue our manifest destiny into the stars, launching American astronauts to plant the Stars and Stripes on the planet Mars.”

This aligns with Executive Order 13914, released during the President’s first term, that announced, “Outer space is a legally and physically unique domain of human activity, and the United States does not view it as a global commons. (Emphasis added) Accordingly, it shall be the policy of the United States to encourage international support for the public and private recovery and use of resources in outer space, consistent with applicable law.”

Defining outer space in the negative, as not a global commons, is legally interesting. The Outer Space Treaty specifically addresses sovereign claims in space, which supports the notion that outer space is outside the jurisdiction of any one nation state.

Putting aside the historical implications of the term, “Manifest Destiny” as a legal framing device might be referring to space as a place rich in resources, ripe for harvest, and with little legal restraints to guide nations and corporations as they venture out into space to claim what they can grab.

As one example, President Trump appears likely to examine federal regulations associated with space launch and recovery – such as speeding up the FAA’s launch and reentry licensing process, such as SpaceX’s Starship program. The FAA is already reviewing the rules for Part 450, the regulation that covers launch and reentry. Will we see more waivers or fast tracks to approvals?

In the meantime, regardless of U.S. domestic legal decisions, space debris continues to pose a risk to current systems dependent upon outer space and the further development of human activities in space.

Tackling the Program Through Technology…Together

What should we do while we wait for consensus? The commercial space industry must be ready to take on the problem of space debris. The Federation of American Scientists propose a variety of technological approaches to manage space debris, including debris-cleaning tech like ground laser nudges, space tugs, space lasers, reusable rockets and maneuverable satellites.

Move It On Over

Certain satellites can adjust their position through a satellite operator, a person or entity that manages a satellite. For example, the International Space Station performed an in-orbit maneuver to dodge debris.

Baked-In Mitigation

Incorporating technological protocols to mitigate debris into satellite development might be one viable option. The Aerospace Corporation, a U.S. independent testing and research center for space systems, uses its 80 specialized laboratories to test, analyze, and troubleshoot virtually every aspect of rocket and satellite systems. That includes space debris mitigation. For example, an Aerospace team developed a prototype deorbit motor to allow space operators to safely retire their spacecraft on demand. This capability and associated protocol must work seamlessly with international organizations and nations to safely coordinate that deorbit.

Tugging Away

A debris management method known as a tug for controlled entry, or uncontrolled re-entry, may be applied to large debris greater than 10 centimeters. In a controlled entry, the tug catches an object and adjusts its orbit so the object re-enters the Earth’s atmosphere at a specific angle to concentrate debris falloff in a concentrated area. The estimated cost of this method runs, on the low end, at about $1,815 per pound ($4,000 per kilogram) and, on the high side, around $27,223 per pound ($60,000 per kilogram).

On the other hand, uncontrolled re-entry catches an object and adjusts its orbit so it re-enters the atmosphere freely with no predesignated fall area and unclear reentry timing. The estimated cost of this is about $1,360 to $18,150 per pound ($3,000 to $40,000 per kilogram). There are no development costs.

Laser Tag…You’re It!

Ground laser nudges may be used on both large and small debris. This method uses a laser to move an object without physical contact from the surface of the Earth and requires a lot of energy. Costs range from $135 to $2,720 per pound ($300 to $6,000 per kilogram) plus development costs of about $600 million USD.

Space laser nudges may be used on both large and small debris. This method uses a laser to move an object without physical contact from space and uses less energy from ground-based lasers as energy will not be lost through the atmosphere. Costs vary from $135 to $2,720 per pound ($300 to $3,000 per kilogram) plus development costs of about $300 million.

Nudging Things Along

At a minimum, scientists appear to agree that small debris should be physically removed and large debris should be nudged aside to prevent collisions. Just in time collision avoidance by way of laser nudges or rapid response rockets are both additional methods specific to large debris. These methods can prevent predicted collisions between large pieces of orbital debris.

Regardless of method used, the positive long term effects of clearing away space debris, while implementing procedures that prevent additional debris piling up to replace that cleared away, will pay dividends over time.

Who is Doing this Work?

As you can see, technological developments to address space junk are costly and include multiple stakeholders.

In 1989, NASA estimated that space junk removal costs could increase in payload-delivery costs by about $15-20 million/ per object and $7.8 million per vehicle. In 2020, the European Space Agency (ESA) partnered with Swiss startup ClearSpace in a $103 million deal to remove a piece of debris from low earth orbit. According to the ESA, this is “the first removal of an item of space debris from orbit.”

ClearSpace-1 is planned to launch in 2028 to remove ESA’s 210 pound (95 kg) PROBA-1 satellite, launched in 2001. The mission was conceived by ESA’s Clean Space team. However, this launch will demonstrate true cooperation between private companies (ClearSpace and subcontractors), international organizations (ESA), and nations (Switzerland). In addition to ClearSpace’s work with ESA, ClearSpace, and companies like Astroscale and Spaceway, are also developing robotic arms, nets and harpoons to capture and deorbit debris.

The ESA / ClearSpace partnership could be the prototype for future similar cooperation in the battle against space junk. We could be on the brink of the establishment of a new and sustainable commercial sector in space.

May The Force Be With You

There are no easy answers when it comes to clearing out space debris. It will continue to be a problem that needs a solution. Forward thinking companies can leverage current technologies to address the issue of space debris head on. Private industry can also partner with policy makers and advocate for change through UNCOPUOS and other like minded organizations.

Costs are significant. Cost projections to develop and implement solutions are likely outside the means of all but nations and the biggest of big companies. However, the framework is in place for corporations to partner with international organizations, governments both local and international, and forward thinking leaders to solve the problem of space junk.

Failure to address the space junk problem could result in severe limitations to access to LEO and the functionality of payloads in low earth orbit. Failure to act will not only cost money, but could jeopardize the ability to truly leverage and develop the burgeoning outer space economy.

Just like that elementary school dodgeball game, we all have to play. And when we play together, we are more likely to succeed.

By: Tracy Reynolds