By: Nate Ernst, AG Energy Ambassador

With the recent move for some operators to utilize a 44807 authorization and the impending publication of the long-anticipated Part 108 notice of public rulemaking (NPRM), the commercial unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) industry continues to evolve on both the regulatory and technology fronts. With this evolution, the demand for heavier, more advanced UAS platforms will naturally increase. However, these systems come with greater complexity and higher costs. One of the most important, yet often misunderstood, considerations is how to strategically select the best system—Group 1, 2, or 3 UAS—for particular operations. While technical specs and mission capability may be the more obvious differentiators, the most important one comes down to the actual business case—the costs and operational constraints—for selecting one group of drone type over another. Now more than ever, understanding the practical, business-driven implications of UAS group selection can make—or break—your UAS program.

Understanding the Groups: A Quick Primer

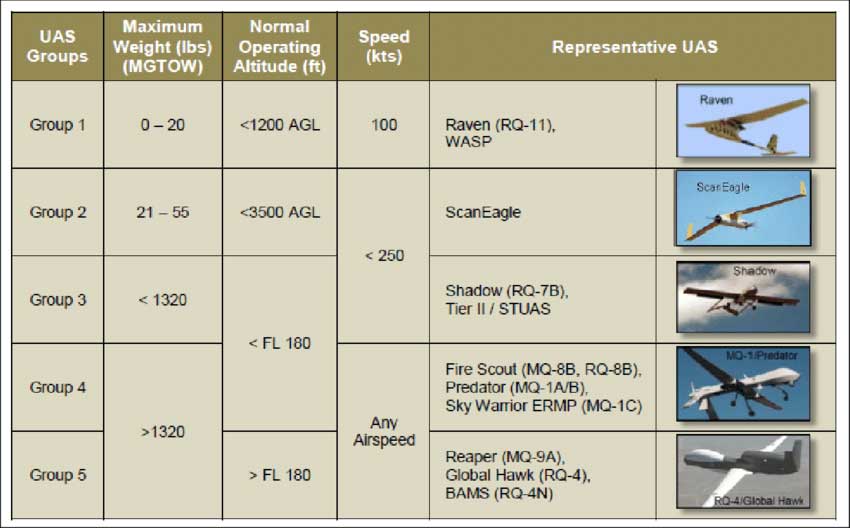

While the commercial UAS industry does not have a formal classification system beyond basic weight limits, the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) has long relied on a well-defined structure: the UAS Group category chart.

Though designed for military use, the DoD UAS Group classification has become a de facto reference point across both government and industry sectors to communicate the relative size, capabilities, and applications of different UAS (groups). The DoD UAS Group chart categorizes unmanned aerial systems into five distinct groups, primarily based on three technical factors: Maximum Gross Takeoff Weight (MGTOW); operating altitude and airspeed. Here’s a brief breakdown of the groups.

Group 1

This group includes small UAS (sUAS) typically used for short-range reconnaissance, surveillance and commercial uses. These drones are often battery-powered, hand-launched and do not require runways. Commercial sUAS operated under FAA Part 107 fall within Group 1.

Group 2

Group 2 drones offer more endurance and payload capacity. These are typically used for longer missions as they are more capable than Group 1 UAS and can carry heavier payloads. They often require some form of launch/recovery system.

Group 3

UAS bridges the gap between tactical UAS and larger strategic systems. They are capable of long-endurance missions and may require more complex launch and control infrastructure.

Group 4

These UAS represent a major jump in strategic capability, supporting long-endurance surveillance. These UAS are highly integrated into airspace management systems and can fly for 24 hours or more.

Group 5

This final group of drones are considered the most advanced and complex UAS platforms in existence, capable of sustained, high-altitude operations across continents. These systems are often equipped with multi-sensor payloads and sophisticated avionics.

The Juice vs. The Squeeze: Business Model Implications

When considering which group of drones to use for a particular mission, one of the key considerations, as the old saying goes, “Is the juice (business case) worth the squeeze?”

Group 1 platforms work best for high-volume, localized operations. If you’re scaling an inspection business that relies on deploying multiple teams across sites—like utilities or telecom—you’ll benefit from the low cost, easy licensing, and minimal regulatory burden of these drones. However, there is an economy of scale at which point Group 1 (sUAS) starts to lose relevance. An operation will become so large that one might ask oneself, “Can I perform an operation at a better scale if I used less (and larger) aircraft?”

Group 2 platforms are typically much more complex than those in Group 1. Operators must be able to justify a business case for the expense of capital, training, competency, and regulatory compliance when weighed against operational benefits. For example, for enterprise customers with large geographic footprints, Group 2 UAS could slash data acquisition timelines. You’re starting to see a prime example of this in the powerline inspection sector. The Scope of Work can be in the hundreds of thousands of structures per year. What originally required 200 Group 1 UAS could be accomplished with 10 Group 2s. While the equipment requirement is slashed by a factor of ten, the operator must decide if the added investment (capital, training, etc.) is justified.

With an even greater amount of operating complexity (and direct capital expense), Group 3 platforms can operate higher and longer than Group 2 platforms. However, most commercial operators in the U.S. National airspace are not equipped to operate these types of systems (yet). This group enables capabilities that are not possible with lighter drones. While breaking into this category may be a true differentiator for one’s business, it will prove to be an incredibly expensive and timely consuming one. the costs associated with training, maintenance, and currency remain relevant but at a higher price point. However, referencing the Group 2 example of powerlines, it is feasible to say that a two Group 3 UAS could replace the capacity of 200 Group 1 UAS.

Choosing the Right Path Forward

To have a viable UAS program, your regulatory alignment, technical performance assessment, and business return on investment (ROI) analysis must guide the decision UAS group selection. An aircraft’s group classification will drive your:

- Licensing path – Most are familiar with licensing requirements for Part 107. In the Group 2 and 3 space, it is very common to be required to hold a private (or commercial) pilot’s license.

- Capital and operational costs – On average, a Group 1 UAS could cost between $3,000 and $40,000. A respectable Group 2 UAS can cost between $75,000 – $250,000. Group 3 UAS start at a general price point of $250,000.

- Crew training and safety case requirements – Operators typical undergo autopilot-specific training, and maintain a pilot’s currency schedule that closely mirrors high performance manned aviation.

- Insurance and risk profile – Insurance companies will insure Group 2 & 3 operations, but this needs to be viewed from the perspective of boutique service. Finding a reputable carrier is not trivial today, as these types of operations are not common just yet. That will inevitably change as more operators begin to utilize these groups of UAS.

It’s critical not to get overly fixated on the group classification of UAS at the outset. Instead, begin with the business case. First identify the ultimate deliverable that your operation needs to achieve. Once you’ve defined that, move to the payload. Determine what equipment or capability the UAS must carry to meet your mission objectives. From there, establish your Concept of Operations (CONOPS). All of this will naturally guide you toward the most suitable group category.

Strategy Drives Success With the FAA’s Section 44807 exemptions providing limited waivers and the upcoming Part 108 framework promising broader regulatory clarity, it will be presumably easier to use Group 2 and 3 UAS. Industry will have to go through another evolution cycle before Group 4 and 5 become viable in the commercial space. However, the bigger these systems get, the more complexity and higher costs they bring. The single largest determining factor of a successful UAS program is understanding your business case. If you understand your business case and combine that with selecting the correct group of UAS, you will have set your program up for success.

By: Nate Ernst