By: Abigail Smith, AG Ambassador

The Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) new proposed rule, Part 146, “Certification of Unmanned Aircraft System Data Service Providers,” lays out a framework for Automated Data Service Providers (ADSPs). While this may sound like just another acronym, it’s actually one of the biggest shifts yet in how the FAA plans to integrate drones into the National Airspace System (NAS).

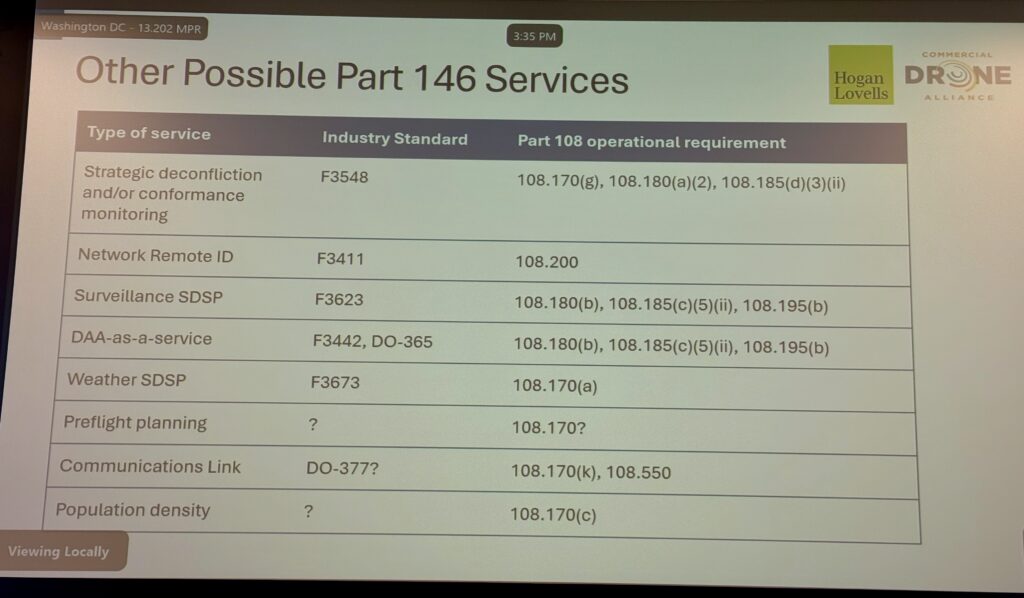

ADSPs will be the companies that will supply the digital backbone, or UAS Traffic Management (UTM), for safe drone operations. These aren’t pilots or operators; they’re the service providers who deliver tools like strategic deconfliction (making sure drones don’t collide in busy skies) and performance monitoring (tracking flights in real time and after the fact). In plain English, ADSPs will provide the data and automation that will make it possible for drones to scale up safely for Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) operations.

The Part 146 (and related Part 108 BVLOS Rules) remain pending and open to public comment. At the recent Commercial Drone Alliance (CDA) BVLOS Stakeholder’s Summit, experts provided their assessment of Part 146, as currently proposed: the good, the bad, the ugly. Here’s what they had to say.

Why UTM Matters

As one expert at the CDA Summit put it, “static maps and self-coordination won’t cut it when you’re dealing with thousands of flights a day.”

UTM essentially equates to the air traffic coordination system for drones. Unlike traditional air traffic control (ATC), it’s designed to be automated, scalable, and flexible. With drone delivery services scaling in cities, inspections increasing in rural areas and public safety teams turning to unmanned systems for urgent missions, the FAA knows that without UTM, the NAS would quickly become congested and unsafe.

Certified ADSPs enable UTM to create a dynamic ecosystem where different operators, from large delivery companies to local first responders, can share the same airspace without stepping on each other’s toes. It’s an essential step forward.

The Good: Modernization and Flexibility

Industry voices at the CDA summit largely welcomed the FAA’s move. Many agreed that nearly 2,000 daily operations already rely on UTM-style services. This proves the model has moved well beyond the hypothetical. UTM is happening now.

They praised Part 146 for recognizing these realities and for offering flexibility. The framework allows for iteration and revision as technology improves. Crucially, it separates service provider certification (the company itself) from service authorization (specific offerings), ensuring accountability at multiple levels. That layered approach mirrors how aviation already handles complex systems.

The Bad: Complexity, Public Safety and Paperwork

Still, not everyone was entirely convinced that Part 146 gets the industry where it needs to go. Summit participants pointed out a few areas where Part 146 risks confusion and over-complexity.

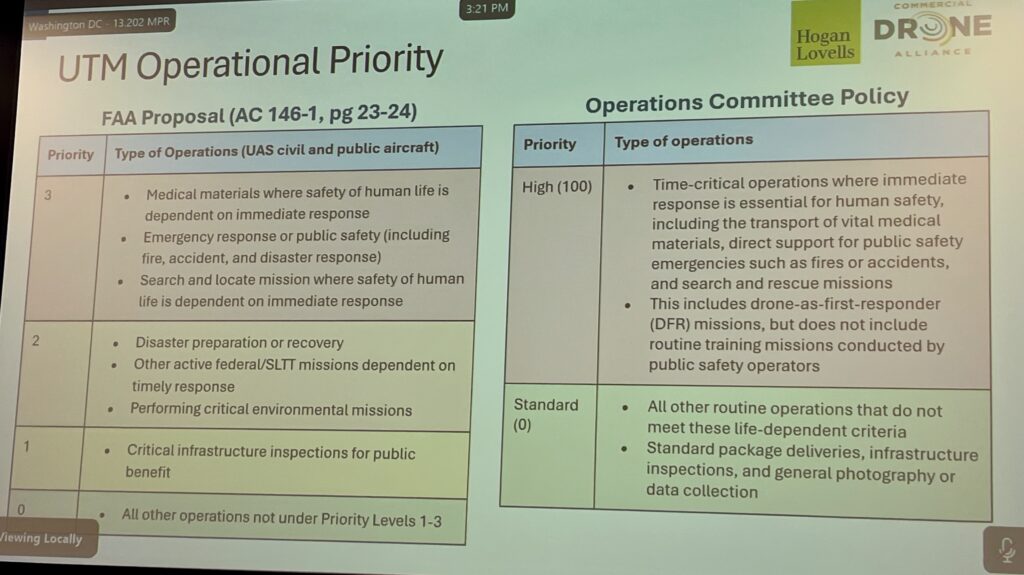

For example, what exactly counts as “strategic deconfliction”? How should it work for emergency responders who don’t fit into rigid scheduling models? Public safety officials worry about getting boxed out by rules that don’t account for their unique, dynamic and often unpredictable missions.

Others raised alarms about reporting burdens. If performance monitoring flags every tiny deviation, like a wingtip drifting inches off a planned path, operators could end up padding their flight plan areas to avoid nuisance alerts. Ironically, that could make the skies less efficient, not more.

The Ugly: Commercial Risks and Market Fairness

Perhaps the toughest critiques focused on commercialization. Some feared that by handing core functions of drone traffic management to private providers, the FAA might “privatize” critical aspects of ATC.

While experts clarified that ADSPs only provide data (not operational control), the concern is real. If service models become too prescriptive, operators may find themselves locked into a handful of large providers. Smaller companies could be pushed out, or face higher costs just to stay compliant.

Interoperability was another sticking point. With so many drone manufacturers and software platforms, integrating everything under one framework could be costly. Those costs may eventually land on the operators.

Collaboration Already Works

One bright spot often overlooked is that U.S. UTM committees have already demonstrated responsible ways to interoperate with one another. These working groups have shown that it’s possible to simplify emergency prioritization. They have successfully prioritized pop up public safety missions, like search and rescue or urgent medical delivery, so that they can automatically take precedence in shared skies.

And because this infrastructure is still so new, there is ample room for many providers to enter the market. We’re not looking at a winner-take-all system. Instead, there’s space for multiple players, each serving different slices of the drone industry. That diversity is a strength. It helps ensure that innovation, affordability and resilience remain at the forefront.

A Market That Works for Everyone

Despite the voiced concerns, there’s strong reason to believe the market will balance itself.

- Large operators may build their own integrated systems or contract premium ADSPs.

- Smaller operators will use modular, affordable plug-and-play services.

- Public safety and first responders will benefit from tailored solutions that prioritize mission urgency.

Competition among ADSPs should keep prices accessible across the spectrum. This will ensure that UTM isn’t just a tool for the well-funded, but rather a service every operator can access.

Imperfect But Essential and Necessary

The CDA Summit made clear that Part 146 is both necessary and imperfect. It’s a forward-looking framework that acknowledges drones can’t be safely scaled without UTM. At the same time, it raises tough questions about fairness, clarity and balance between public responsibility and private innovation.

In my view, the takeaway is simple: UTM is essential to the safety of the NAS. Without it, we risk chaos. With it, we get a flexible, evolving system that protects the skies and enables growth. Yes, there will be growing pains. But the direction is the right one.

The FAA has opened the door. Now it’s up to industry, regulators and operators of all sizes to shape this system into something that works for everyone.

Don’t Miss Your Chance to Comment

The FAA is currently taking public input on the Part 146 Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM). The comment period closes on October 6. This is the opportunity for drone operators, manufacturers, service providers and community stakeholders to share perspectives that can shape the final rule.

The FAA takes all comments into consideration. Thoughtful feedback, whether it’s about technical feasibility, economic impact, or public safety, can directly influence how the rule is finalized. If you care about the future of drone integration, now is the time to make your voice heard. And don’t forget, when you comment, don’t just focus on the bad and the ugly. Tell the FAA what’s good and what should remain in that rule, just as I did in this article. (See prior AG coverage on providing impactful NPRM comments). If you care about the future of drone integration, now is the time to make your voice heard.