By: Dawn Zoldi

TruWeather Solutions is turning the U.S. Department of Transportation’s 2025 Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) National Strategy, Recommendation 2.8 into an operational, low‑altitude weather framework for AAM, drone and counter‑drone operations. Backed by seven years of real-world data, a weather data collection, fusion and analytics software system and a performance-based ASTM standard the company helped author, TruWeather is testing and demonstrating a scalable solution to address a major disrupter to achieving reliable and efficient future flight operations: weather.

In this exclusive interview, TruWeather Founder and CEO and retired U.S. Air Force weather leader Don Berchoff explains how the company is enabling emerging AAM operators to move from concept to confident, repeatable flight.

The Groundwork: Part 108 Weather “Risk” and ASTM Standards

Berchoff outlined the backdrop to the current policy landscape for AAM. He said that when the FAA drafted the Part 108/146 Notice of Public Rulemaking (NPRM) for drones, it did something “historic.” It elevated weather from a background “hazard” managed by pilots to an unquantifiable risk requiring better digital weather data collection to understand the true risk backed by real weather observations for uncrewed operations.

In the NPRM, the FAA explicitly recognized the low altitude weather gap that Berchoff has been warning industry about for years. Once an aircraft leaves a METAR (Meteorological Aerodrome Report) location, the relevance of that airport weather can rapidly degrade on days when the weather is not “severe-clear and calm.” The agency also noted that only about 3% of U.S. airspace has approved weather observations within a 5‑nautical‑mile radius of the airport METAR. This leaves the system effectively “blind” between airports below 5,000 feet.

Berchoff saw this gap decades ago, in the military as an operational Meteorologist, weather center commander, and Air Force base commander, and later at the National Weather Service, when he occupied a high-ranking Senior Executive Service position. The legacy aviation weather grid (two balloon launches a day plus airport METARs), he noted, simply does not resolve microscale winds, fog, turbulence or urban canyon effects in the first 5,000 feet where drones and eVTOLs will actually fly. He built his company specifically to address this problem. But he did more than that. He also shaped the rules to facilitate the solution.

Specifically, Berchoff helped lead the ASTM F38 Weather Working Group and has been a key contributor to ASTM F3673‑24, the first consensus weather data performance standard for drones, with applicability to air taxi and helicopter operations. This standard focuses on Weather Information Providers (WIPs), aka. third‑party weather providers, and shifts the emphasis from certifying each sensor to meeting performance standards for weather observation data and services (accuracy, latency, traceability, and metadata) regardless of whether the inputs are METARs, inexpensive IoT stations, wind lidars, cameras or airborne sensors.

Dovetailing with these standards, the NPRM now recognizes weather as a distinct Automated Data Service Provider (ADSP) function. That recognition ends a prior short-sighted approach that positioned weather providers as “supplemental.” Under the FAA’s emerging ADSP framework, weather data sits on par with tactical deconfliction and other automated services.

This critical reframing creates a regulatory home for third‑party, performance‑verified weather data. A revision to the ASTM F3673‑24 will publish a Means of Compliance that can inform the draft Part 146 for non‑federal, low‑altitude weather networks to be qualified, monitored, and integrated into traffic management and operator decision tools. This opens a certification path for providers to leverage third-party weather data and add another safety layer to reduce risk at low altitude.

Building Blocks: AAM Strategy and The Comprehensive Plan

The USDOT AAM National Strategy and its companion Comprehensive Plan build on the recent policy moves that document the criticality of more granular and precise weather measurements between airports for drone and air taxi operations. The Strategy elevates weather infrastructure to one of four foundational infrastructure pillars, right alongside physical, energy and spectrum.

Recommendation 2.8 of the Strategy, titled “Develop enhanced weather detection, forecasting, and reporting network capabilities for AAM operations,” crystalizes this. It calls for several interlocking elements:

- Interdependent low‑altitude networks, including vehicle to vehicle

- Airborne weather data collection from AAM aircraft

- Predictive and decision tools and

- Standards for third‑party providers

The Comprehensive Plan then threads these requirements through the full LIFT action framework to move AAM from early ops to a mature system between roughly 2026 and 2036. Specifically, LIFT directs Federal agencies to:

- Leverage existing programs and testbeds in the near term to start building low‑altitude sensing networks and decision tools with commercial tech and third‑party providers.

- Initiate deeper research, standards work and SLTT (state, local, tribal, territorial) planning to define performance requirements, qualification paths and funding models for interdependent sensor networks and ADSP‑grade weather services.

- Forge new policies, regulations and consensus standards that make those microscale weather networks part of the baseline AAM infrastructure, not a sidecar.

- Transform the system by scaling those networks nationally, fully integrating third‑party weather providers into cooperative‑area operations, and moving from simple nowcasting to high‑resolution, short‑term forecasting that is embedded in traffic management and operator decision‑support systems.

In other words, the Plan uses LIFT to turn 2.8 (low altitude weather) from a single paragraph in the Strategy into a decade‑long implementation roadmap that assumes commercial sensors, public-private weather networks and performance‑based standards are central to how AAM will actually fly.

TruWeather has aligned itself, with its V360 architecture, as a ready‑made 2.8 / LIFT execution vehicle through its physical‑plus‑digital platform that already aggregates sensors, models and tools in live testbeds to achieve compliance with the standards Berchoff helped to forge.

Seven Years Of Real Data: Proof Of The “Weather Tax”

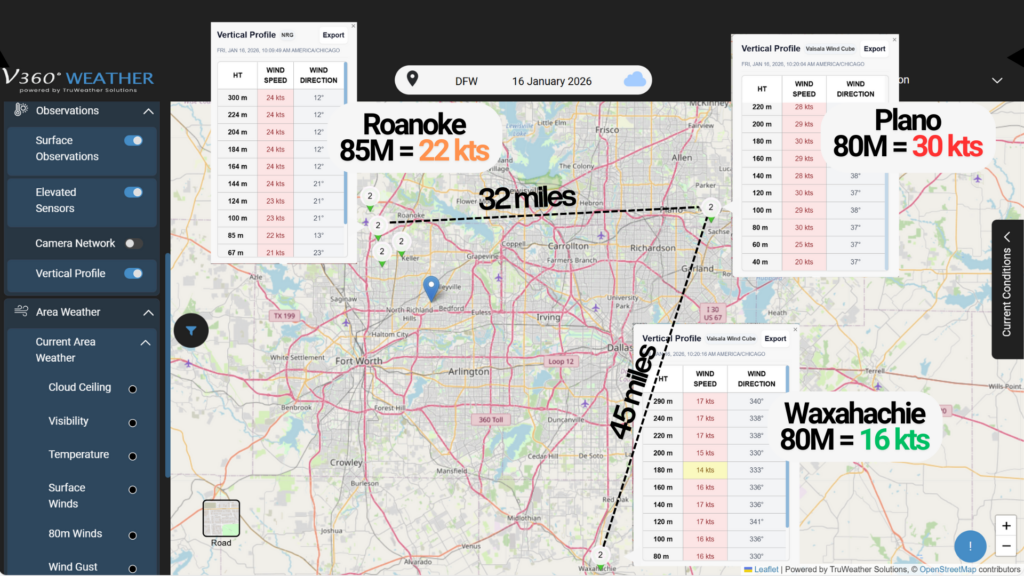

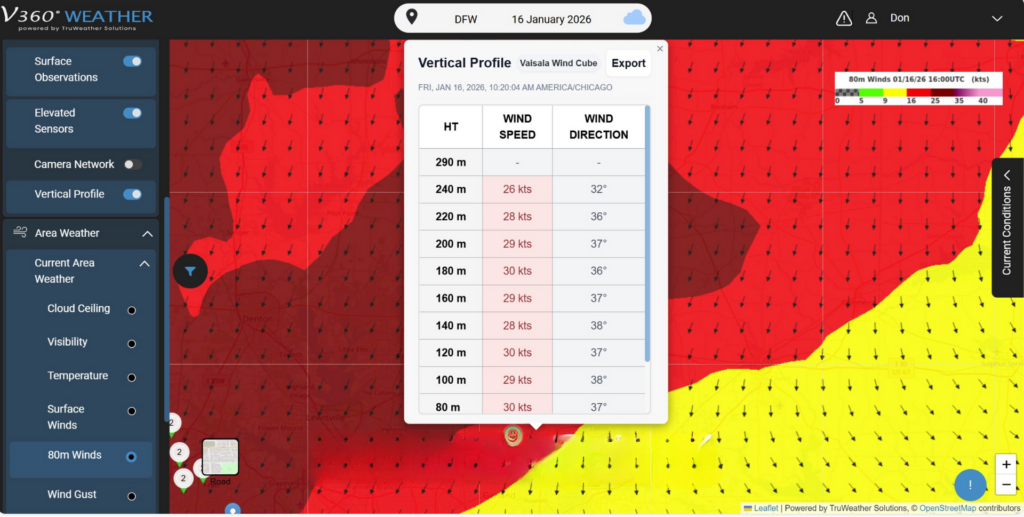

During the interview, Berchoff provided an unplanned, adhoc demo of his tech as it monitored the weather over the Dallas–Fort Worth network to illustrate why real data, not just models, remain central to both safety and economics.

On 16 January the wind varied at 80 meters or approximately 250 feet above ground level across the Dallas-Ft Worth metroplex from 16 Knots at 250 feet at Waxahachie, Texas, to 22 Knots at Roanoke, Texas and 30 Knots at Plano, Texas. The best government model forecast at the same time estimated 21 Knots at Plano, underestimating the wind field by 48% and 27 Knots at Roanoke, an 18.5% overestimation error. According to Berchoff, while the models generally are not off by this magnitude, 5 to 10 Knot errors, along with wind direction errors, occur often enough that without real wind measurements to validate and correct the models, pilots may mission plan for a larger range of wind possibilities.

Why does this matter? For battery‑limited cargo drones or air taxis, that uncertainty causes operators to carry excess power reserve, shed payload, reduce distance (when another option exists) or accept higher diversion risk. The cost of this uncertainty increases —the “weather tax” Berchoff has been talking about: you either don’t fly when you can safely, or you fly with less payload. This impacts revenue generation per aircraft and service reliability. TruWeather’s motto is “keep them flying in as close to 100% of safe operating windows as possible while maximizing payload and power efficiency.”

TruWeather today is running a Street‑Scale Wind Analysis and Prediction System (SWAPS) model every hour in demonstration mode near Alliance Airport in Ft Worth. SWAPS today uses the uncertain government model for initial wind conditions to input into a Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD)-based digital twin to “see” wind flows impacted by the urban landscape that weather models cannot discern today. In the next year, SWAPS will be infused with real weather measurements from an array of wind lidars and other surface and elevated wind data to improve the precision, accuracy and validation of SWAPS. With the TruWeather demonstration in Ft Worth, the promise of how microscale wind intelligence, can:

- Cut reserve margins by quantitatively narrowing the range of wind uncertainty.

- Increase payload and seat‑mile economics on flyable days.

- Reveal hidden “no‑go” corridors and vertiport approach paths on adverse days before operations ever launch, or vice versa, dynamically route flow in “sweet” airspace for power optimization and smoother rides for clients.

This is the kind of quantified performance that maps directly into 2.8’s requirement for “dynamic decision‑support tools.” It gives the FAA, NASA and DOT the datasets they need to codify future weather performance standards.

Para. 2.8, De‑Risked: How TruWeather Tracks The Requirements

With a seven‑year head start, TruWeather maps line‑by‑line to the AAM Strategy and Plan requirements. In fact, Berchoff claims his company could assist in pulling the federal 2026‑2036 timeline forward by three to five years.

Enhanced Detection – Real Sensor Networks

TruWeather has purpose‑deployed networks of surface stations, ceilometers/visibility sensors and vertical profilers (including an unprecedented six wind lidars) in places like Fort Worth–Dallas and California corridors. The company designed this sensor network specifically to fill the “between airports” gap from the surface to 5,000 feet AGL. It not only monitors the sensors and reports outages to clients operating today, but plans to tag the metadata to show where, when, how and by whom each observation was generated, in alignment with ASTM F3673 data‑performance provisions.

Enhanced Forecasting – Urban Wind Modeling

The company’s SWAPS downscales regional Numerical Weather Prediction (NWP) into a CFD‑driven digital twin at 250‑meter and finer adaptive resolution. It captures building‑scale shear, channeling and directional shifts around vertiports and corridors. TruWeather will soon begin assimilating real lidar and sensor data into those models to correct instances of 5–15‑knot errors in baseline grids and direction errors of 30–45 degrees that materially affect performance, separation and trajectory planning.

Reporting & Decision Tools – From Raw Data To Go/No‑Go

The V360 platform fuses heterogeneous data into a single, “integrated weather picture” and exposes it through mission‑centric dashboards, alerts and APIs. These translate technical weather into route‑ and vertiport‑level go/no‑go, and enable operators to translate into power‑reserve guidance with enhanced precision. TruWeather is using a NASA‑funded testbed in Fort Worth to prototype Minimum Operational Procedures (MOPs) and metadata schemas that regulators can adopt as a practical means of compliance for ADSP weather services.

Interdependent Networks – Public, Private and Airborne

The company has architected networks that integrate state‑owned, municipally funded and private investor sensors and can ingest third‑party weather feeds or operator‑owned stations, which matches the Strategy’s call for public‑private, interdependent low‑altitude networks. A TruWeather’s Army SBIR Phase II project will soon test “working drones” equipped with sonic anemometers to feed real‑time wind data into the diverse weather sensor data cloud.

Operationalization & Scale – 90‑Day IOC, 3‑Year FOC

Executive Order 14307’s eVTOL Integration Pilot Program (eIPP) is the federal vehicle to turn the AAM Strategy and Comprehensive Plan into living ecosystems: state‑ and city‑led “economic engines” that must stand up operations within 90 days and then iterate for three years. TruWeather has committed to an Initial Operational Capability within 90 days of an agreement by aggregating existing proprietary sensor data, regional networks and other weather partner commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) integrations, then closing key sensing gaps over the three‑year eIPP period.

eVTOL Integration Pilot Program: Embedded “Micro-Weather Bubbles”

The FAA must select at least five eIPP projects by March 3, 2026. TruWeather reports being on multiple eIPP team submissions, covering 24 states. If the bids TruWeather is part of succeed, these eIPP ecosystems will become the proving grounds where ASTM F3673 performance standards, ADSP certification pathways, and Recommendation 2.8’s low altitude weather network all converge in real revenue‑generating flight. It will also give the company a broad footprint to “cut and paste” weather infrastructure, what Berchoff referred to as ”Micro-Weather Bubbles,” across geographies. As of mid‑January 2026, the down‑select has not yet occurred.

Regardless, as AAM scales toward 2030 and beyond, TruWeather’s AAM National Strategy 2.8‑aligned approach delivers several cross‑domain benefits:

- AAM & eVTOL: Higher dispatch reliability and more predictable power management for air taxis, including regional routes, especially in complex urban terrain and around vertiports. Add to this better separation standards and cooperative‑area operations, because wind, gust, and turbulence fields are actually measured and forecast at the altitudes where these aircraft fly.

- UAS & BVLOS: Enabling Part 108 and other BVLOS approvals that can reference ASTM F3673 and consensus-based weather performance instead of relying solely on sparse FAA aviation weather networks. TruWeather also supports scalable UTM/UTM‑like constructs with machine‑to‑machine weather feeds that match other ADSP data in reliability and auditability.

- Counter‑Drone & National Defense: Micro‑weather intelligence that helps DHS and defense users understand when friendly counter‑UAS assets can fly—and when adversary drones are likely constrained—creating what Berchoff calls “weather superiority” over key urban areas. It also provides shared data that can inform airspace security operations for marquee events like FIFA, the Olympics, and high‑value urban targets, where low‑altitude traffic and atmospheric conditions will both be highly dynamic.

By design, TruWeather’s low‑altitude sensor networks and archiving of real data do more than just satisfy policy language. They operationalize it as a measurable, certifiable capability by turning weather from an unpriced tax on operations into a managed, monetizable performance edge for AAM, drones and the systems that protect them.