By: Dawn M.K. Zoldi

Robotics has moved from glossy CES stages and magazine covers into energy plants, construction sites and, increasingly, living rooms and hospitals. Autonomy Global Network’s Full Crew Episode 76, hosted by Autonomy Global’s Ambassador for Europe, Joanna Wieczorek, tackled the reality of robotics in 2026. It’s not about sci‑fi humanoids taking over the planet. It’s about robots, behind-the-scenes and on the daily, taking on hazardous, dirty and dull work, powered by “physical AI” and designed around human safety, usability and business

Safety First in Hazardous Work

Nowhere is robotics more mature, or more necessary, than in hazardous industries. The Energy Drone and Robotics Coalition (EDRC) alone counts roughly 20,000 members worldwide, with about 300 energy and utility companies actively deploying robots and drones to improve safety and reliability across nuclear, mining, oil and gas, refining and power. EDRC Managing Director Sean Guerre summed up the sector’s priorities. “Over the 10 years of the energy drone [and] robotics coalition, the number one reason for use cases, whether it’s proof of concept or scaling, is safety,” he said.

The article the Full Crew panel examined, “How Robots and AI Reduce Workplace Injuries by 50% in Hazardous Environments” (Blockchain News), details how AI‑enabled robots, equipped with computer vision, thermal sensors and machine learning, remove people from high‑risk tasks such as working at height, inside confined spaces and in harsh environments. The piece cites a McKinsey Global study projecting that combining AI with robotics in hazardous industries, “particularly looking at construction,” could prevent up to one million workplace injuries annually worldwide by 2030.

That is not science fiction; it is the business case, Guerre noted. Major oil and gas firms like Shell, Chevron, BP, ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips, downstream operators such as Valero and Marathon Petroleum, and utilities including Duke Energy, PG&E, Exelon and Florida Power & Light already use aerial, ground and subsurface systems for surveying, mapping and inspection. (See prior AG coverage of autonomous drones and robotics in energy).

This safety logic has spread to Europe as well. Energy players such as Orlen, TotalEnergies and Engie leverage drones and robots to monitor pipelines, power plants and other critical infrastructure. They often explicitly tie these deployments to ESG strategies and sustainability reporting.

Physical AI, in this context, provides the enabling layer that lets robots perceive complex sites, understand risk and adapt autonomously enough to keep humans out of harm’s way while keeping assets online.

Kimberly McGuire, a robotics engineer and founder, sees similar opportunities in aviation and healthcare. Exoskeletons for baggage handlers and hospital staff may not look like traditional robots, but they are robotic systems that “integrate with the human itself” to reduce musculoskeletal injuries from repetitive lifting.

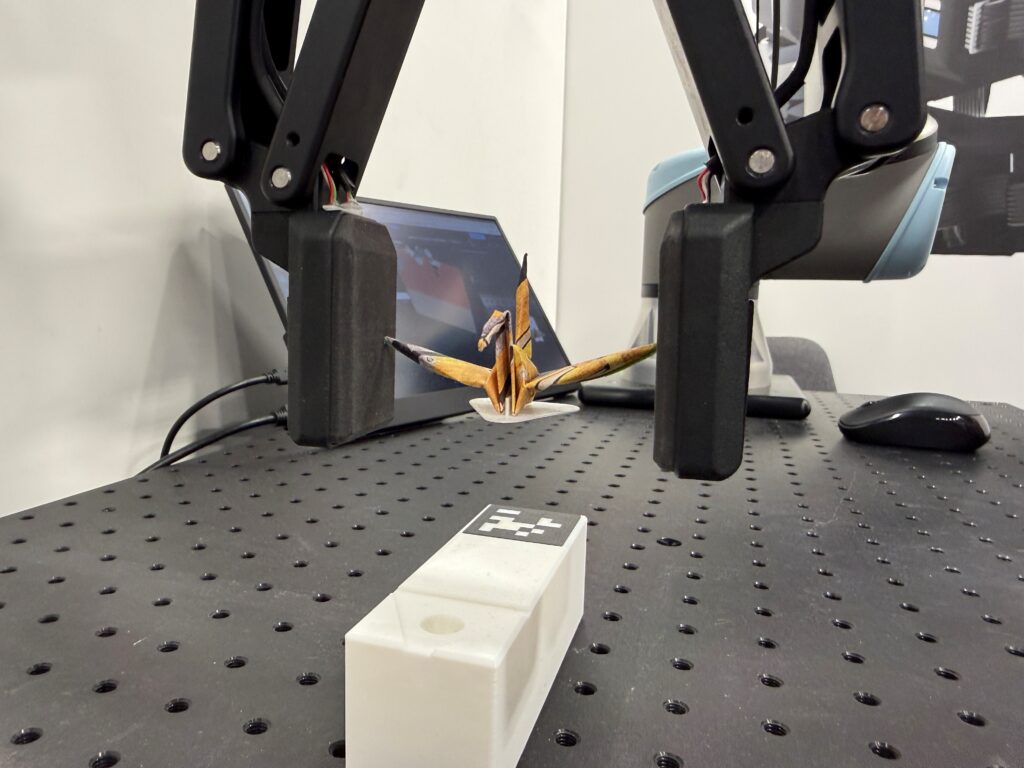

Dr. Alexander Schmitz, CEO and co-founder of XELA Robotics, connected his company’s value proposition to this same world of hazardous, fine‑scale work. He explained that XELA’s tactile sensing helps automate tasks such as cable insertion and bolt‑tightening, which remain surprisingly manual and accident‑prone across industrial and construction‑adjacent settings. (See prior AG coverage of XELA Robotics from CES). Rather than replacing workers, robots absorb the physical punishment so humans can work longer, safer and in more skilled roles.

From CES to the Living Room

If heavy industry shows where robotics is working now, CES 2026 offered a preview, sometimes awkward, sometimes delightful, of where it wants to go next. An Engadget feature, “The robots we saw at CES 2026: The lovable, the creepy and the utterly confusing,” chronicled a show floor where robots “took center stage” at what is still primarily a consumer technology event. Humanoids danced, did karate, climbed and washed stairs, picked up children’s toys and, in some cases, unloaded and folded laundry.

For McGuire, the fact that robots dominated CES is itself a signal. Robotics is “really brewing” and attracting serious investment far beyond industrial niches. She pointed to 1X (formerly Halodi Robotics), founded in Norway and now globally headquartered in Palo Alto, with its humanoid “butler” as emblematic of this transition where machines shaped like people will become commonplace in homes and public spaces rather than just in cages on factory floors. As working mother and aviation lawyer Wieczorek put it, the idea of a robot that “go[es] to your living room and pick[s] up the toys from the carpet,” folds laundry or washes staircases feels like a “must have” rather than a gimmick.

But the CES article and panel also exposed current limits. Many of the most impressive robots operated only in carefully staged demo zones, with constrained interactions. Some could be hugged, some explicitly could not. Tasks like folding laundry or tidying rooms were performed “very very slowly,” which reduces the value proposition for everyday users. And a wave of viral “beauty robots,” such as hairdressers, estheticians, nail technicians, all proved to be AI‑generated fakes, which highlights how marketing can get ahead of engineering.

More importantly, some of the most advanced systems lean heavily on cloud AI. McGuire raised a simple safety question around this point. “What happens when the Wi‑Fi goes off? What does the robot need to do?” A large robot that loses connectivity cannot simply “turn around like a Roomba,” especially around children or fragile objects.

In aviation, standards and concepts of operations already spell out what a drone must do on GPS loss or link loss. For household robots operating around children, pets and fragile objects, similar fail‑safe behaviors will be essential. Wieczorek, who spends her days navigating BVLOS, SORA and other drone frameworks, expects a comparable “huge debate about law” for domestic and service robots as they move from trade‑show curiosities into homes and public spaces.

On the concept of social acceptance, XELA Robotics’ Schmitz remains cautiously optimistic. He believes people “are ready to give a shot” to domestic robots, but only if basic conditions are met: safety, non‑threatening appearance and, above all, genuine utility. “A lot of robots that are out there now…are still not very useful,” he observed. Even laundry‑folding robots may be “too slow to be actually useful.” For elder care, one of the most promising and sensitive applications, robots will have to be “super easy to use,” he said, because “not everybody is always tech savvy.” That resonates well beyond CES. If a lawyer immersed in technology, like Wieczorek, describes setting up a floor‑cleaning robot as a “nightmare,” consumer robotics still has a usability mountain to climb.

The “Just Enough” Robot

Perhaps the most provocative of the Crew’s articles, a New York Times profile titled “He’s the Godfather of Modern Robotics. He Says the Field Has Lost Its Way,” centered on Rodney Brooks, often dubbed the “godfather of modern robotics,” whose ideas have shaped decades of robotics research and commercialization. Brooks argues that the field is over‑rotating toward general‑purpose humanoids and human‑level performance, when in most cases “we don’t need a human level performance to create value.”

Schmitz shares that view on the ground. In industry, he noted, customers routinely choose simple grippers over sophisticated humanoid hands, because “simple grippers…are cheaper, more reliable and good enough.” Walking robots attract headlines and funding, but “very often a mobile base…on wheels” is better suited to indoor logistics, where floors are flat and paths are predictable. The real frontier, in his assessment, is not walking, but touching. Much of the world’s labor in 2026 remains stubbornly manual (think: cable insertion, seating memory in motherboards, warehouse pick‑and‑place) and these tasks are “very labor intensive” and “very straining for humans,” yet still hard to automate with vision alone.

This is where tactile sensing, the “sense of touch” for robots, comes in. “When you want to actually grasp, hold and manipulate objects, vision is often not enough. You cannot see the inside of your robotic hand once you close it…[and] the sense of touch can help you to automate those kinds of things,” Schmitz explained. XELA’s sensors give robots that capability, enabling more reliable assembly, bolt‑tightening and, in the near future, tasks like harvesting delicate fruit or loading dishwashers without breaking dishes. It is a very Brooks‑ian answer to the humanoid hype cycle: make robots good at the specific physical interactions that create value, rather than obsess over perfect human imitation.

Brooks’ concerns extend beyond form factor to behavior around people. Robots that “don’t know how to behave near human beings” risk causing harm or sparking public backlash, just as drones used in conflict zones have changed how some communities perceive all unmanned aircraft. Wieczorek sees a shared mission for the autonomy ecosystem: to educate the public on positive use cases and to design systems, and regulations, that make those benefits tangible and trustworthy.

At the same time, humanoid form factors are not going away. As McGuire pointed out, a lot of cutting‑edge AI for robotics relies on human‑in‑the‑loop and imitation learning: training robots from footage or demonstrations of humans performing tasks. Because “we have five fingers and we have a full body,” mapping human motions onto non‑humanoid platforms remains nontrivial. Some companies respond creatively by putting human trainers in robot‑like grippers, forcing them to “pick up the glasses as the robot should with the same constraints,” thereby generating data that better matches the robot’s morphology. This kind of ingenuity hints at a middle path between Brooks’ “just enough” machines and the drive for humanlike dexterity.

For operators of critical infrastructure, the answer may simply be: all of the above, as long as the business case works. Many refineries, offshore platforms and power plants were designed for human workers and will operate for decades, making humanoids attractive because they can navigate ladders, doors and controls without expensive retrofits. In contrast, greenfield “dark factories” can be optimized around robots on rails, tracks or wheels that “may not require the full humanoid or even a humanoid at all.” Guerre captured the unifying principle of the conversations when he said, “Technology for tech’s sake doesn’t work.” He continued, “For us, it really comes back to what is the challenge that potentially could be solved…Once the business case is proven, then you can apply the technology to it.”

That logic carries into medicine. While XELA is not a medical device company, its customers already experiment with tactile sensors for palpation, “to find tumors like a human would do,” and surgery, where today’s robots still lack true force feedback. As outcomes data accumulates and robots demonstrate they “don’t have a bad day” or “shaky hands,” patients undergoing high‑risk procedures may decide that a robot‑assisted surgeon, equipped with better sensing, is not a threat but a safeguard.

In the end,all three experts converged on a pragmatic vision of robotics’ future:

- Schmitz said XELA is “working towards more complete solutions…not only providing the hardware but also software [and a] complete solution that makes it very easy for everyone to use,” especially in settings like elder care and households.

- McGuire urged investors and industry to “focus on those companies that actually are trying to solve problems instead of following the hype.”

- Guerre, speaking for large‑scale energy and infrastructure operators, reiterated that scaling robotics comes down to clear use cases, proven safety and tangible ROI.

Threaded through it all was Wieczorek’s call to action: “We need to start somewhere.” From offshore wind farms and refineries to CES show floors and agriculture, the next decade of robotics will be defined not by humanoid hype, but by physical AI‑driven machines that make work safer, smarter and more human‑centric…one exoskeleton, tactile sensor and floor‑washing stair climber at a time.