By: Joanna Wieczorek, AG Europe Ambassador and Yves Morier*

In a digitally connected world, almost every industry depends on networks, data and automation. Aviation, associated with rigorous safety standards, has been confronted since a while to a new and evolving challenge: cybersecurity. As uncrewed aircraft systems (UAS) integrate into civil airspace, their digital backbone has become both a technological marvel…and a target. From unlawful interference to state-sponsored attacks, Europe’s regulators, industry and research organizations continue to work together to ensure that the growing civil drone ecosystem remains secure and trusted. Here’s how.

The Expanding Risk Landscape

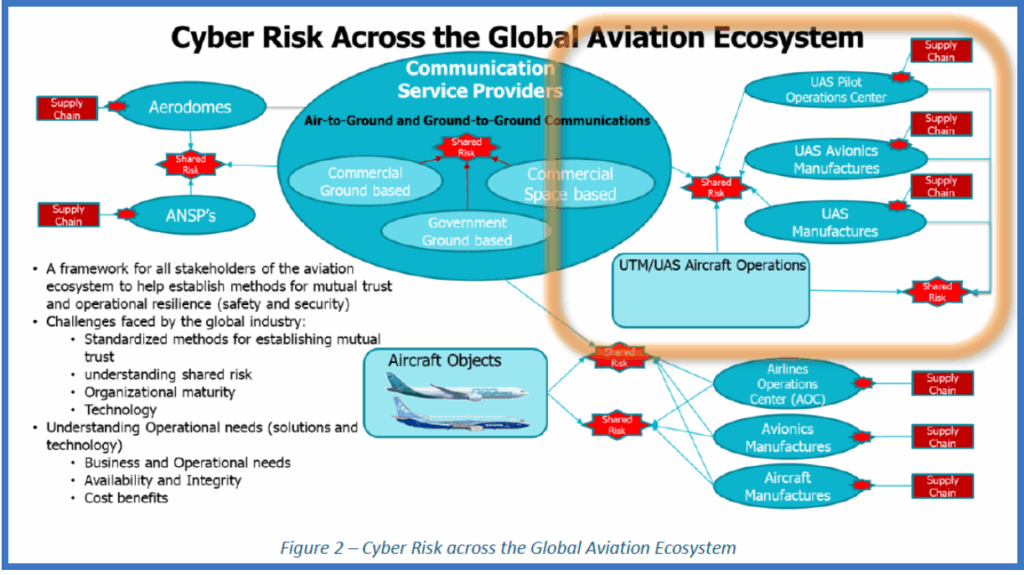

Drones represent one of the most connected technologies in modern aviation. They collect, transmit and process enormous amounts of data (sometimes sensitive, often real-time) and rely on command, control and communications (C3) links and satellite systems to operate safely. As with any networked device, vulnerabilities abound. A successful cyberattack could hijack control, steal payload data or disrupt navigation. Worse, large-scale interference with the Unmanned Aircraft Traffic Management (UTM) systems, known in Europe as U-space, could paralyze drone operations across one or more U-space airspaces.

The supply chain adds another layer of complexity. Each sensor, chipset or software module presents a potential entry point for malware or data corruption. A single infected component, introduced early in production, can compromise multiple downstream systems. Regulators have recognized that a single weak link could compromise an entire ecosystem.

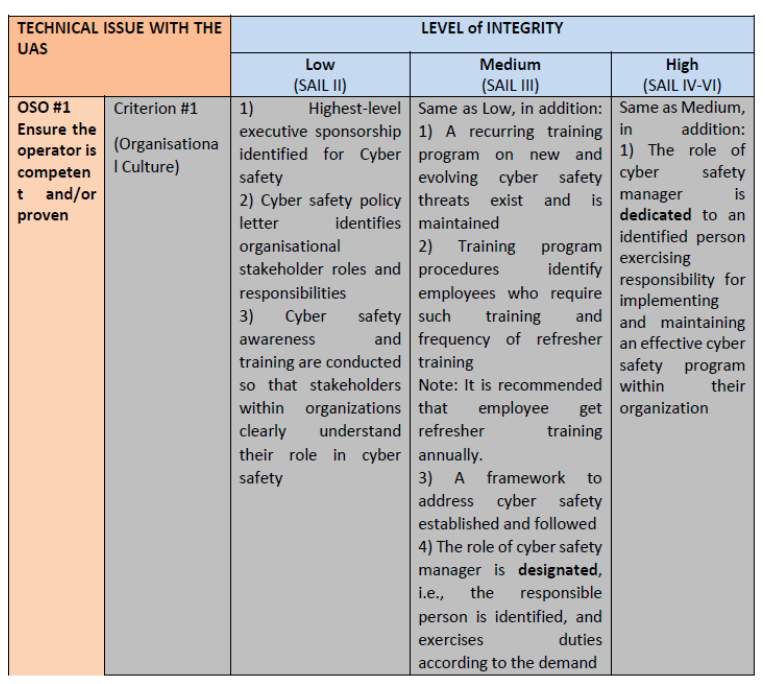

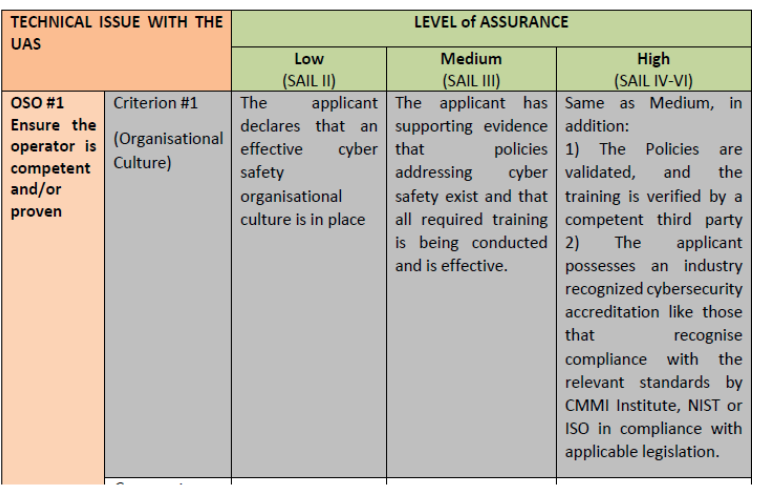

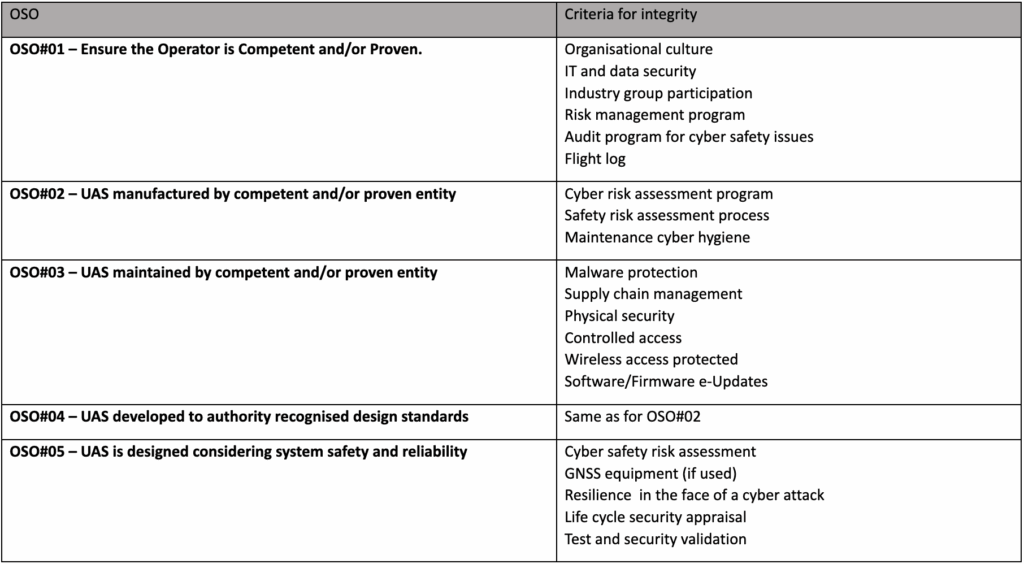

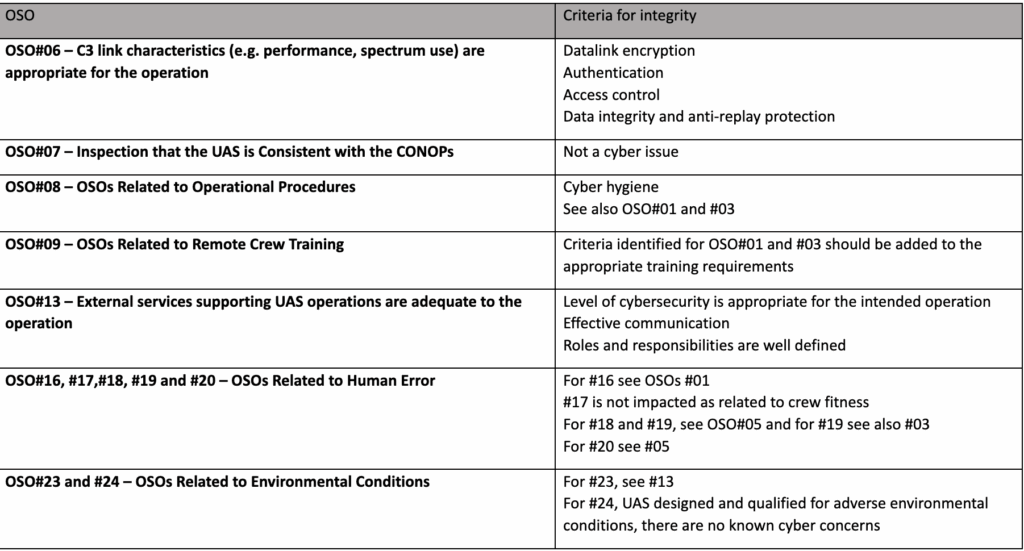

From Safety to Cyber-Safety: JARUS and SORA

The Joint Authorities for Rulemaking on Unmanned Systems (JARUS), a global cooperative of aviation authorities including EASA, FAA and Transport Canada, has guided UAS risk management. Its cornerstone framework, the Specific Operations Risk Assessment (SORA), helps determine the necessary mitigation measures for an operation based on ground, air and fly-away risks. Each operation is assigned a Specific Assurance and Integrity Level (SAIL), from I to VI (I being low and VI being high), which dictates the rigor of required safety controls called Operational Safety Objectives (OSO) in SORA.

While SORA initially focused on physical safety, recent developments have expanded its scope to include cyber threats. The JARUS Cyber Safety Extension translates cybersecurity principles into safety controls. It defines key protection attributes (e.g., confidentiality, integrity, and availability) alongside management requirements for authentication, authorization and accountability. Cybersecurity-by-design, least privilege access and secure-by-default configurations have become central tenets.

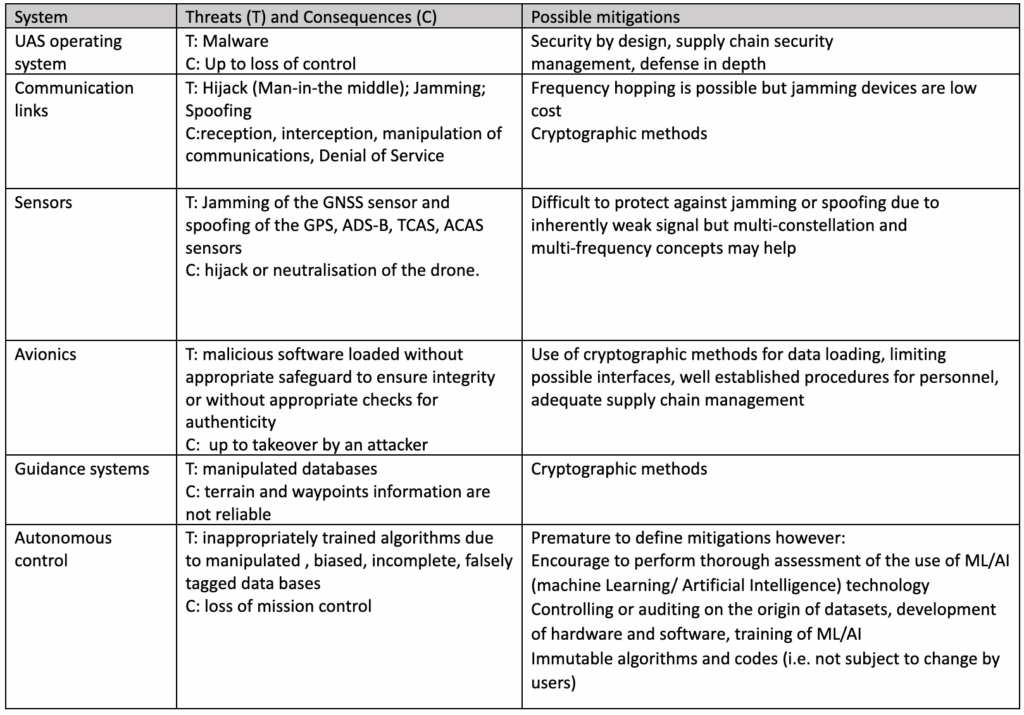

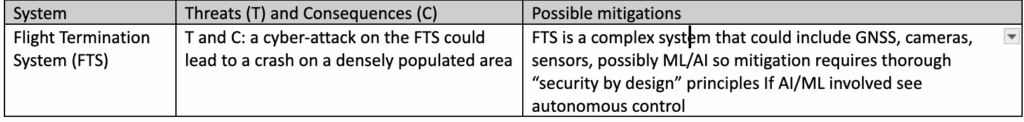

The updated SORA guidance examines attack vectors such as denial-of-service disruptions, jamming and spoofing of GNSS signals and man-in-the-middle hijacking of communication links. It also highlights how malware could enable external actors to seize control of a UAS, turning it into a tool for surveillance or destruction. For each domain, from operating systems to avionics, specific controls include encryption protocols, resilient control architectures and comprehensive operator training.

Regulations Anchored in Security

European regulation has evolved alongside these frameworks. Under Regulation (EU) 2019/947, UAS operations fall into open, specific and certified categories, each with different obligations. While basic security references apply to open-category drones, devices in higher classes (C2 and C3) must include protected communication links resistant to unlawful interference. Remote identification modules, required in classes C1 through C3, must also be tamper-proof.

For higher-risk operations, the specific category demands that operators implement procedures to prevent unlawful interference. Drones in the Class C5 and C6 used for Standard Scenarios (STS) must also comply with the requirements for links and remote identification described above.

U-space operations take this further: both Common Information Service Providers and U-space Service Providers must install full security management systems. States must perform security risk analyses before airspace approval. These measures ensure that cybersecurity is woven into airspace architecture and not treated as an afterthought.

Complementing regulation, EUROCAE (the European Organization for Civil Aviation Equipment) has become a backbone of UAS cybersecurity standardization. Its Working Group 72 (Security) defines airworthiness security processes applicable to both manned and unmanned systems. Its WG-105 (UAS) focuses on C3 links to ensure their resilience against digital interference.

Research and Innovation: Strengthening the Digital Shield

Cutting-edge research amplifies Europe’s regulatory progress. Within the SESAR program, the SECOPS project is testing an integrated security model for drone operations. By simulating unlawful interference at the Netherlands RPAS Test Centre, the initiative explores technologies to strengthen navigation and surveillance systems, protect third parties and integrate geo-fencing into cybersecurity frameworks. The goal is clear: to make UTM security both verifiable and adaptable.

Meanwhile, the European Union Space Program Agency (EUSPA) has advanced drone security through the Galileo satellite system and its Open Service Navigation Message Authentication (OSNMA) service. Projects like DEGREE and GEODESY have successfully tested flight controllers incorporating OSNMA to ensure that positioning data transmitted to drones cannot be spoofed or falsified.

Adding to this momentum, the European Space Agency’s NAVISP initiative, carried out by Unifly and Nexovia, performed live jamming and spoofing simulations to evaluate new certification schemes for secure UTM services. This resulted in a prototype UTM platform compliant with the majority of Security Assurance Requirements (SAR). Future research, building upon these results, will extend beyond controlled environments into real-world validation.

Last but not least, ENISA, the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity, is the Union’s agency dedicated to achieving a high common level of cybersecurity across Europe and all domains.

Looking Ahead: A New Technological Horizon

As Europe prepares for a networked, autonomous future, cyber defences must evolve with equal speed. The rollout of 5G and emerging 6G communications promises unprecedented data rates and low-latency links, but expands exposure to advanced threats such as quantum-enabled attacks and cross-border data exploitation. Regulators and technologists recognize that each leap in connectivity brings new vulnerabilities.

Artificial intelligence (AI) compounds this dual-edged challenge. While AI can bolster cybersecurity through predictive anomaly detection and autonomous threat response, it also enables more precise and adaptable attacks. The line between defender and aggressor continually shifts. This increases the need for constant vigilance in the use of machine learning and automated systems across UAS ecosystems.

To unify these efforts, the European Union (EU) has introduced the voluntary “Trusted Drone” concept under its Drone Strategy 2.0. The concept is under development now. Comparable to the United States’ Blue UAS framework, the initiative would provide assurance to users that the labelled drones have been verified and found secure enough to be used in more critical or sensitive operations. The overall resilience of the system to cybercrime would thus be improved.

Countering the Flip Side: Drones as Cyber Threats

While defending drones from cyber risks remains essential, Europe is also addressing the inverse problem: drones as potential cybersecurity weapons. With the ability to carry compact, high-resolution sensors and transmitters, they can be deployed for espionage, signal interception or direct interference with communications systems. Reports of drones surveilling sensitive sites or targeting energy and data infrastructure have grown steadily across the continent.

To combat this, the European Commission’s Defense Readiness Roadmap 2030 includes the European Drone Defence Initiative, a coordinated “drone wall” that blends detection, tracking and interception technologies across member states. This network will protect not only against military incursions but also against unmanned intrusions that could threaten critical assets. Its backbone will synchronize with NATO systems and establish Europe’s first integrated counter-drone defense architecture by 2027.

Building a Culture of Cyber Resilience

The progress in regulatory frameworks, technology and defense systems would mean little without human resilience. Operators remain the keystone in this security edifice. JARUS guidance now emphasizes “cyber hygiene” as operational doctrine. This equates to a commitment by pilots, maintainers and manufacturers to ensure that secure practices form part of everyday workflow. This cultural shift includes regular training, vulnerability testing and information-sharing among UAS stakeholders.

Still, challenges remain. Confidentiality issues often inhibit the open exchange of threat intelligence across borders and industries. Establishing trusted platforms for sharing, while safeguarding proprietary or security-sensitive information, will be central to improve collective defences. The EU’s evolving cybersecurity apparatus, under entities like ENISA, is playing a key role in coordinating these efforts.

A Shared Responsibility for a Connected Future

The European civil drone ecosystem stands at a turning point. The technologies enabling safe, efficient and innovative flight are the same ones that expose it to cyber vulnerability. Through collaborative regulation, forward-looking research and strong institutional partnerships, Europe has begun crafting a comprehensive response that aligns technological ambition with digital safety.

Cybersecurity is not simply a checklist item. It is an enabler of public trust. The systems being put in place now will shape how society interacts with autonomous aircraft for decades to come. By safeguarding the skies, Europe is doing more than protecting machines. It is protecting the very foundation of a connected, intelligent and secure aerospace future.

*Yves Morier graduated from the French Civil Aviation Academy as an Air Transport Engineer (MSC) in 1975. After his military service, he joined the French CAA (DGAC) in 1979. He was seconded as Regulation Director to the Joint Aviation Authorities (JAA) in 1993. In 2004, he joined EASA where he occupied several management posts. His last assignment was as Principal Advisor New technologies to the Director of Flight Standards where he contributed to the development of the first EU regulations on drones. He retired in 2019 and since then has remained involved in Drones and Advanced Air Mobility, mainly as a volunteer.