By: Jason Day, AG Public Safety Ambassador

The FAA’s proposed Part 108 rule signals a defining shift for drones in American airspace, especially for public safety agencies looking to expand beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS) operations. By laying out a framework for routine BVLOS use, Part 108 sets the stage for new operational categories, certification pathways and risk-based standards that will dictate how law enforcement, fire services and emergency responders integrate drones into daily missions.

But as with the rollout of Part 107 nearly a decade ago, the Notice of Public Rule Making (NPRM) is only the beginning. The final rulemaking process will likely involve significant revisions, informed by public comments, stakeholder advocacy and real-world operational feedback. For public safety leaders, this is a critical window to engage, influence and ensure that the final rule reflects the unique needs and realities of our lifesaving UAS missions.

How FAA Part 108 Changes Drone Operations for Public Safety

The FAA’s proposed Part 108 rule represents a major shift in how BVLOS operations are regulated by transitioning from a waiver-based system to a standardized framework that enables routine, scalable missions for search and rescue (SAR), disaster response and tactical overwatch.

The NPRM stratifies operations into five categories based on population density, ranging from rural (Category 1) to dense urban cores (Category 5). Public safety missions in higher-density areas will face stricter requirements, including operating certificates, detect-and-avoid (DAA) capabilities for non-cooperative aircraft and FAA oversight for strategic flight deconfliction.

Remote pilots will need to hold a Part 107 certificate and obtain a Part 108 rating, supported by additional training in command-and-control (C2) systems, DAA protocols, and BVLOS-specific safety procedures. (See prior AG coverage on Part 108 and training).

The rule also introduces TSA-led security vetting. It would require agencies to ensure that personnel meet aviation-style clearance and background check standards. Together, these provisions signal a more structured, but potentially burdensome, path forward for public safety UAS operations. (See prior AG coverage on Part 108 security requirements).

Data Sharing For the Win!

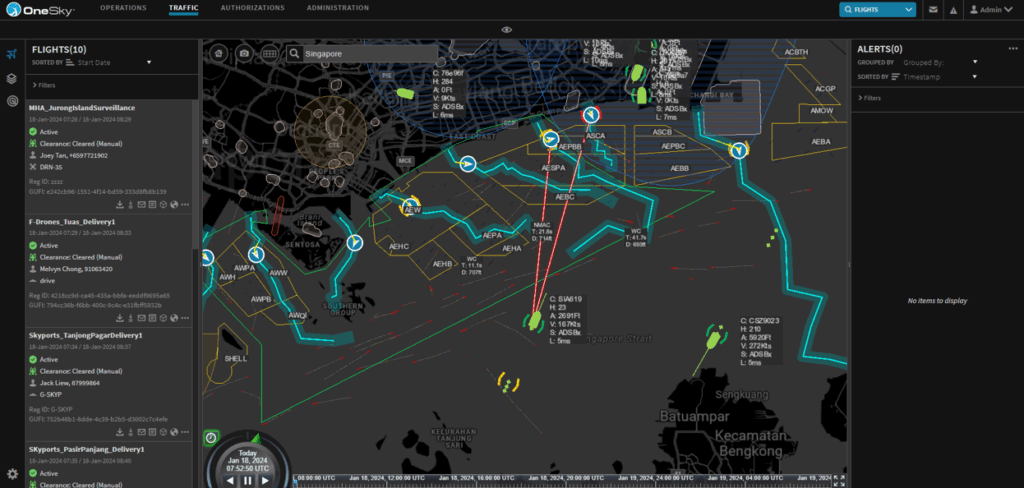

One of the most promising aspects of the FAA’s Part 108 NPRM is its emphasis on data sharing, which could deliver the biggest win yet for public safety UAS operations. As agencies increasingly rely on drones for complex missions, the need to visualize the airspace in real time has become critical, not just for safety, but for strategic coordination.

The NPRM’s proposals to expand and formalize data sharing through secure online portals and interoperable systems lay the groundwork for a complete, dynamic picture of the national airspace. This directly supports the maturation of the UAS Traffic Management (UTM) system, where NASA and the FAA have actively engaged public safety stakeholders, including the Arlington Police Department and the Texas Department of Public Safety, particularly focused on the DFW Keysite. Agencies across North Texas are helping shape UTM capabilities to meet the demands of tactical deployments, mass gathering events and emergency response.

In Texas, the proliferation of the Team Awareness Kit (TAK) has been an incredible accomplishment. It has demonstrated how real-time data sharing and visualization within a single pane of glass can dramatically increase situational awareness, reduce risk and enhance mission effectiveness. As Part 108 moves forward, its data-sharing provisions could finally unify commercial and public safety airspace users under a common, transparent framework that elevates safety and operational efficiency across the board.

However, the federal government and commercial UAS stakeholders must recognize that public safety agencies, particularly smaller departments, remain tragically underfunded and often lack the resources to participate meaningfully in emerging systems like UTM. While Part 108 and the broader UTM framework promise enhanced safety through real-time data sharing, that vision cannot be realized unless there is a dedicated financial mechanism to support the integration of first responder UAS data. Without funding for equipment, connectivity and platform interoperability, many agencies could remain invisible to the system. This would create dangerous blind spots in the national airspace and undermine the rule’s purpose.

What Stakeholders Are Saying: Concerns on FAA Part 108

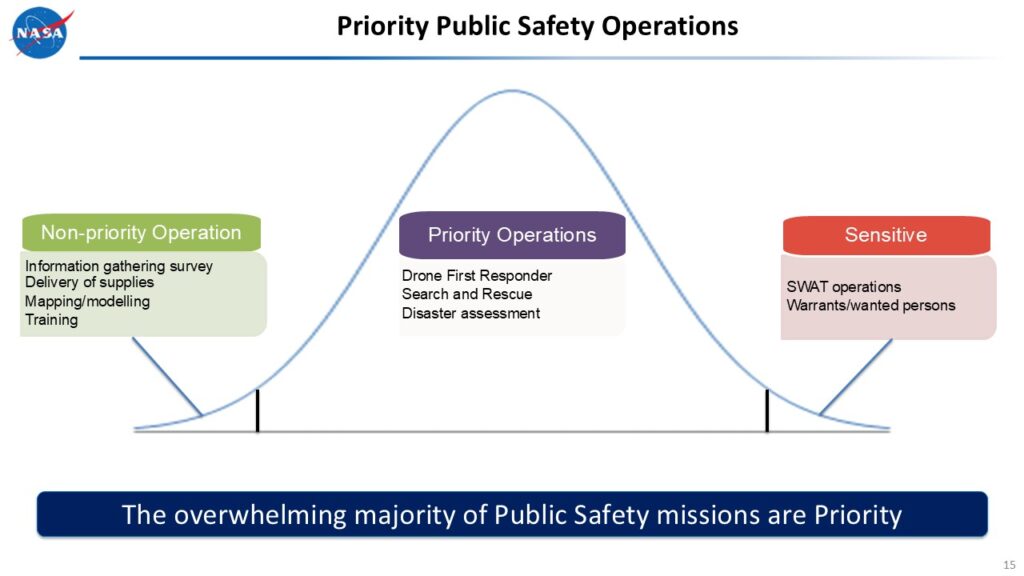

While the FAA’s Part 108 NPRM aims to establish a regulatory framework for BVLOS operations, many in the public safety community are concerned that the proposal is disproportionately focused on commercial drone delivery and autonomous fleet operations. The rule appears tailored to preplanned, automated missions, which contrasts sharply with the dynamic, human-directed nature of public safety deployments that often occur in unpredictable, high-stakes environments. (See prior AG coverage of Part 108 and small organizations’ concerns).

The operational burden introduced by new requirements, such as permits, TSA-led personnel vetting and population-based risk categories, could be cost-prohibitive and logistically complex for smaller agencies, especially those conducting daily tactical flights. (See prior AG coverage of the delta between real ops and Part 108). Unfunded mandates have the very real potential to cripple public safety UAS programs. When federal regulations impose new compliance requirements without providing financial support, agencies are forced to absorb costs they simply cannot afford.

Moreover, the proposed elimination of the current Part 107 waiver system threatens to stall innovation in programs like Drone as First Responder (DFR). Many agencies, including the Fort Wayne Police Department, have invested significant time, resources and operational expertise into developing DFR programs under Part 107 BVLOS waivers. Yet the current language in Part 108 appears to nullify those efforts, requiring that all future BVLOS operations, even for public safety, conform to the new regulatory framework regardless of prior approvals or proven success. (See prior AG coverage of Part 108 and first movers). The rule also risks excluding non-governmental responders such as volunteer fire departments and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) SAR teams. This would sideline critical community-based capabilities.

Finally, the integration with Automated Data Service Providers (ADSPs) for strategic deconfliction presents technical hurdles, without offering a clear mechanism for public safety to gain priority access to the National Airspace System (NAS) during emergencies.

Airspace Management: Why Are Prioritized Zones Missing?

Public safety stakeholders have expressed deep disappointment that the FAA’s Part 108 NPRM failed to designate any form of priority airspace for UAS, despite years of advocacy and operational precedent. Many in the UAS community had anticipated that airspace at or below 200 feet AGL would be formally recognized as the primary domain for unmanned operations, a concept supported by NASA’s UTM research and widely viewed as a practical step toward safe integration.

While such a designation would undoubtedly be a difficult adjustment for manned aviation, especially in low-altitude environments, it remains a necessary evolution to ensure the safety and scalability of the NAS. Without clear altitude separation, public safety agencies are left to navigate increasingly complex missions without the structural support needed to deconflict with other airspace users. The absence of this provision in the NPRM not only complicates strategic planning but also undermines the potential for more advanced, lifesaving UAS operations to flourish within a predictable and protected framework.

Industry Unity on FAA Part 108: One Voice for Public Safety

As the FAA moves toward finalizing Part 108, I cannot overemphasize that this rule will shape the future of BVLOS operations for years to come and impact the very fabric of public safety response.

National organizations like DRONERESPONDERS are dedicating immense time and energy to ensure that public safety agencies are represented in these discussions by advocating for equitable access, operational flexibility and mission-critical infrastructure.

But ultimately, decisions are made by those who show up. It is essential that public safety professionals, large and small, urban and rural, lend their voices to the rulemaking process. Together, that voice can be powerful. Only you can shape a regulatory framework that protects the public, empowers responders and ensures that lifesaving UAS operations are not just permitted…but prioritized.